- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Visitor Regulations

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- The Republican Settlements of El Brujo: Notes for the Recent History of Magdalena de Cao

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

PUCP Archaeology Students Visit the El Brujo Archaeological Complex ...

The Salinar on the North Coast of Peru ...

To receive new news.

By: Yuriko Garcia Ortiz y José Ismael Alva Ch.

The fall of the Spanish colonial government system in Peru, driven by the emancipatory movement between 1809 and 1825, achieved the independence of the most important cities in the territory: Trujillo, Lima, Cusco, Huamanga, Arequipa, and Huánuco, along with the defeat of Viceroy La Serna.

During the transition to independence, Trujillo experienced a combination of continuity and change. Although the city played a fundamental role in the struggle for independence and saw the emergence of new political figures, it also maintained many of its colonial social and economic structures, especially regarding the power of the landowning elites and the persistence of a stratified society. Independence, therefore, did not mean a total break with the colonial past, but a complex process of adaptation and transformation under the presidency of new political figures (Contreras, 2020).

The Chicama Valley in the 19th and Early 20th Centuries

The economy in the Chicama Valley at the beginning of the late colonial period (1700-1821 CE) seems to have improved with the increase in sugar estates (haciendas), the production of fabrics and soaps, local trade, mining, and market investment (Reymundo, 2021, p. 66). However, in the first 100 years of the Republic of Peru, land possession shifted, causing new social tensions.

In the first decades of the inaugurated Republic of Peru, a large part of the haciendas recorded by Miguel Feijoo de Sosa at the end of the 18th century declined over time due to inheritances and, especially, purchases by foreign capital focused on sugarcane production (Armas, 1935, p. 109; Klaren, 1976). Subsequently, after the War of the Pacific, foreign capital modernized the old sugar mills, establishing them as the largest and most important in the valley: the agro-industries of Casa Grande, Roma, and Cartavio. In contrast, the concentration of land in the hands of a few owners brought other social problems related to water access and trade structures (Klaren, 1976).

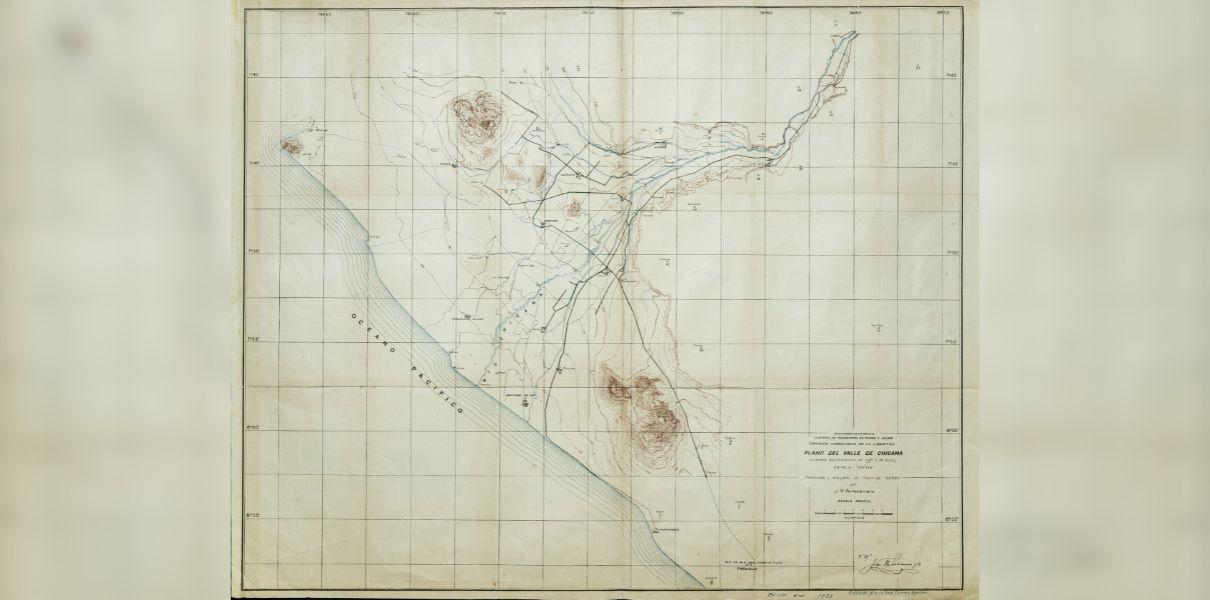

Figure 1. Map of the Chicama Valley on the north coast of Peru. Plan drawn by Charles Sutton and Juan Portocarrero in 1921. Archive: Pontifical Catholic University of Peru.

Magdalena de Cao: The Transition to the Republic and Travelers' Testimonies

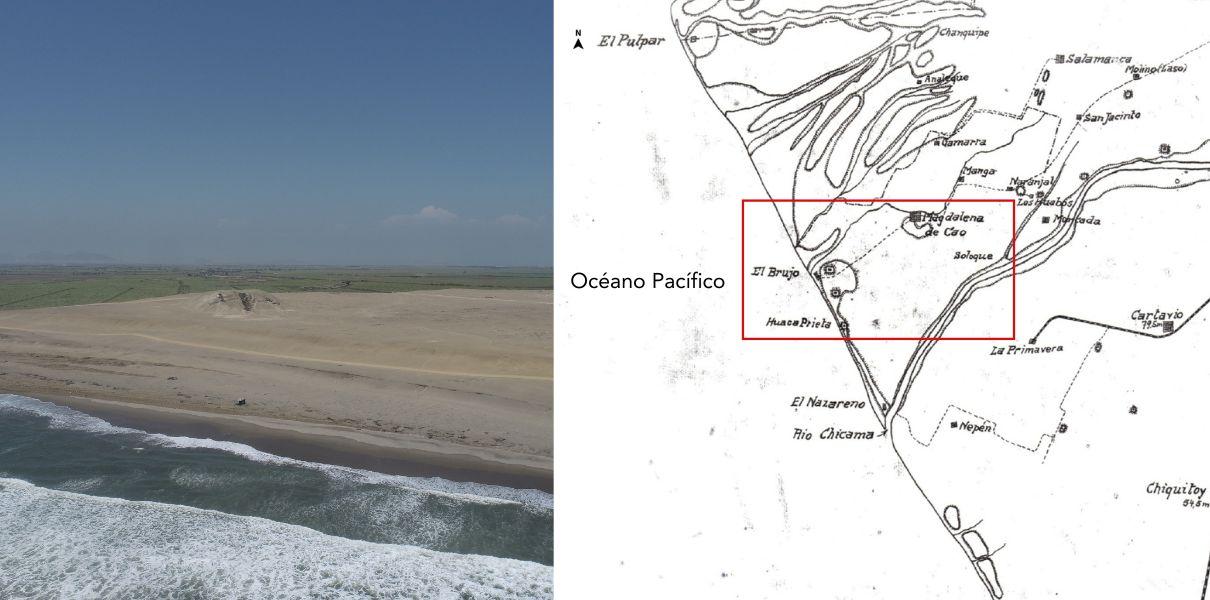

Throughout its history, the town of Magdalena de Cao had three distinct locations. The first, estimated in the mid-16th century, was located near the Chicama River. After an El Niño Phenomenon, the town resettled at the northern end of the El Brujo Archaeological Complex until 1760, when the inhabitants of Magdalena de Cao moved to their current location (García Rosel, 1941; Quilter, 2016). From this last episode onwards, the ruins of the second location of Magdalena began to be called "Pueblo Viejo de Cao" (Old Town of Cao) (García Rosel, 1941; Raimondi, 1868).

The new location of Magdalena de Cao was visited by the first foreign travelers who arrived in our country in the early decades of the republic. For example, the German merchant Heinrich Witt arrived in the town on May 8, 1842, during his journey along the north coast of Peru. Passing through the Chicama Valley, he described the old Magdalena as an isolated town of little prominence in the geopolitical ordering of the basin (Mücke, 2015: 471).

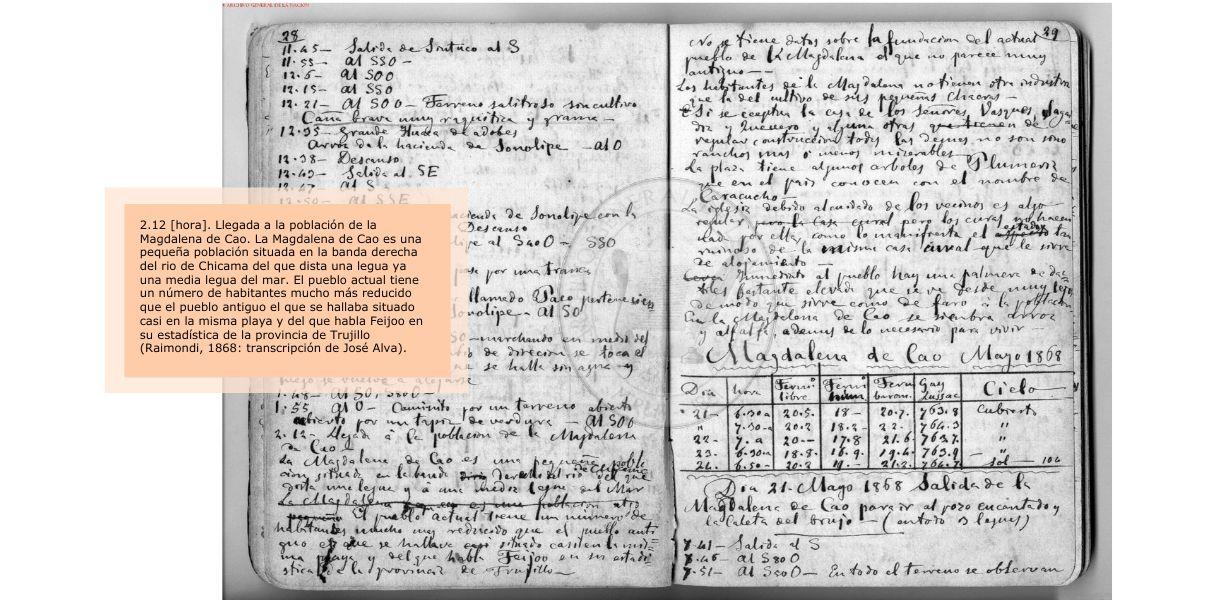

Almost twenty years later, in 1868, the Italian naturalist Antonio Raimondi visited the Chicama Valley, and his stay in the town of Magdalena de Cao marked an important antecedent for the area's history. Raimondi arrived in Magdalena on May 20 and stayed there for about four days.

Figure 2. Itinerary of Raimondi's visit (1868) to Magdalena de Cao and the huacas of El Brujo. Image: General Archive of the Nation.

The Italian naturalist noted that the main economic activity of the inhabitants of Magdalena de Cao was subsistence agriculture, developed on small plots for the cultivation of rice, alfalfa, and other local consumption products. Regarding infrastructure, the town was not extensive, and its dwellings were mostly precarious, except for certain houses of wealthy families. The plaza had some caracucho trees, appreciated for their ornamental flowers. The church was in a ruinous state due to the limited management of the religious order at the time (Raimondi, 1868).

One aspect Raimondi highlighted was the small population of Magdalena de Cao. Perhaps a clue lies in the recruitment of labor in the haciendas through the enganche policy (a system of indentured labor). According to the newspaper La Crónica, the population of the entire district had decreased notably due to the obligations contracted by its inhabitants after the payment of advances (La Crónica, 1918, p. 100).

In the specific case of the town of Magdalena de Cao, demographic records show that in 160 years its population had practically no major variation. For the 1780s, Bishop Baltasar Martínez de Compañón recorded 333 inhabitants (Martínez Compañón, 1985, p. 5r). In Republican times, the population census of 1862 indicated the presence of 458 residents (Paz Soldán, 1877, p. 557). Subsequently, in the 1940 census, the town had 349 inhabitants distributed in 65 families (Ministry of Finance and Commerce, 1944, p. 34).

Aerial photos taken by the National Aerophotographic Service in 1943 show us the characteristics of the town of Magdalena de Cao during the first half of the 20th century. One of them (Figure 3) shows the presence of few houses along the main street (today Av. Miguel Grau), which leads to the town square. South of the square is the church, on whose block no other buildings exist yet. The same occurs on the block where only the municipal building was located. At the northern end is the Magdalena de Cao cemetery, which was inaugurated shortly before Raimondi's visit (Raimondi, 1901, p. 10).

Figure 3. Aerial views of the town of Magdalena de Cao in 1943 (Left) and 2024 (Right). Note the increase in houses in the area delimited by large cultivation areas. Images: National Aerophotographic Service and Google Earth.

The "El Brujo" Cove: Compiling Fragments of its History

Raimondi (1868) and 19th-century maritime sailing directions (documents with navigation route instructions) provide information about the El Brujo cove (formerly called San Bartolomé), west of the huaca currently known as Cortada or El Brujo. In 1860, this cove was enabled so that the community of Magdalena de Cao could ship fruits, charcoal, and firewood (García y García, 1863; Melo, 1906; Raimondi, 1901, p. 10). The first shipment was made on the brigantine "Trujillo" on February 6 of that year (Raimondi, 1901, p. 10). However, the shipment of goods was abandoned before the end of the decade, given that strong swells and the rocky shore caused dangerous situations (Melo, 1906).

Despite this, the cove continued to be occupied in the summer season by residents of Magdalena de Cao and nearby haciendas, for fishing and recreation (Raimondi, 1874, pp. 323-324). At the beginning of the 20th century, it was common to see fishermen from the El Brujo cove entering the sea to fish on their caballitos de totora (reed watercraft) (Stiglich, 1918, p. 161).

A map drawn by the German R. Stappenbeck in 1929 reveals the trace of the road that linked the town of Magdalena de Cao and the cove. This road crossed the El Brujo Archaeological Complex, specifically in front of the south side of Huaca Cortada, and then descended towards the old ranches.

Figure 4. Detail of the road connecting the town of Magdalena de Cao and the El Brujo cove (Stappenbeck, 1929).

Aerial photos taken in May 1943 also recorded the existence of a few fishermen's houses, arranged on an elevated area that guaranteed safety from swells (see Figure 5). Subsequent images taken in 1969 show that, in less than 30 years, this settlement was abandoned and never reoccupied. The reasons for the occupants' departure are not known for now. However, it is currently possible to observe the quincha (wattle and daub) foundations of the houses of the Magdalena de Cao neighbors, who dedicated themselves to fishing and shellfish gathering for generations.

Figure 5. Aerial view of fishermen's dwellings in the vicinity of the El Brujo cove, very close to Huaca Cortada, in 1943. Image: National Photographic Service.

The Fishermen Community of Huaca Prieta: Tales from Our Grandparents

The history of the El Brujo Archaeological Complex is inseparably linked to the communities of the Magdalena de Cao district. The Villegas family still keeps in their memory the stories of Don Raúl Villegas Roldán, the first inhabitant of the current fishing settlement located near Huaca Prieta, south of the El Brujo Archaeological Complex.

In late 2024, we spoke with Maximina Villegas Pacheco (80 years old) and her husband, Francisco Asencio Alfaro (90 years old). Both live in a cozy little house facing the sea, where they gather shellfish and fish with other members of their family. Doña Maximina is the daughter of Don Raúl Villegas, who built his first house in the first half of the 20th century and dedicated himself to fishing on caballito de totora. She also told us that Don Raúl participated in the excavations of Huaca Prieta with the American archaeologist Junius Bird in 1946. Maximina especially still remembers her father's instructions to stay away from the excavations and the materials recovered during those first scientific interventions at El Brujo.

For his part, Don Francisco told us about the bounties of the sea off the coast of the archaeological complex. As a fisherman, Don Francisco recalls with nostalgia that a long time ago fish were abundant in the area, to the point of being constantly trapped at low tide. That moment was perfect for catching fish and gathering shellfish. He indicated that the old salt flats near Huaca Prieta provided the essential ingredient for salting fish, an activity that sought to dehydrate the meat to prolong its preservation. Don Francisco also remembered the presence of life (a type of catfish) in the irrigation ditches of yesteryear. This freshwater fish was very tasty when prepared in sudados (stews) and fried.

Figure 6. Doña Maximina Villegas and Don Francisco Asencio, members of the fishing community on the beaches near Huaca Prieta, kindly shared their experiences with us.

The El Brujo Archaeological Complex: Repository of the Recent Past

The El Brujo Archaeological Complex preserves part of the history of the men and women who inhabited the region over 14,000 years. Currently, its intangible zone, declared by the Ministry of Culture, protects the historical evidence of the old fishing settlement at the El Brujo cove. This zone is material testimony to the history of the Magdalena de Cao district in the 19th and mid-20th centuries; specifically, of those people who developed their social life between the sea and the huacas of El Brujo.

Furthermore, testimonies from neighbors like Doña Maximina Villegas and Don Francisco Asencio bring to the present fragments of history surrounding the El Brujo Archaeological Complex and the changes our ecosystem has suffered. The anecdotes and fantastic stories around El Brujo, which will be the subject of future installments, are part of the collective memory and social recognition of these places that constitute our community's heritage.

References

Armas, J. (1935). Guía de Trujillo. Tipografía “Olaya”.

Contreras, C. (2020). Introducción. In C. Contreras (Ed.), Compendio de Historia Económica del Perú IV: Economía de la primera centuria independiente (p. 11-18). IEP.

García Rosel, C. (1941). Diccionario de la Demarcación Política del Perú (1821-1941). Sociedad Geográfica de Lima.

García y García, A. (1863). Derrotero de la Costa del Perú. Establecimiento Tipográfico de Aurelio Alfaro.

Klaren, P. (1976). Formación de las haciendas azucareras y orígenes del APRA. Instituto de Estudios Peruanos.

La Crónica. (1918). Diccionario Geográfico Peruano.

Martínez Compañón, B. J. (1985). Trujillo del Perú: Vol. II (Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional).

Melo, R. (1906). Derrotero de la Costa del Perú. Guía Marítimo-Comercial. C. F. Southwell.

Ministerio de Hacienda y Comercio. (1944). Censo Nacional de Población y Ocupación 1940.

Mücke, U. (Ed.). (2015). The Diary of Heinrich Witt (Volume I). Brill.

Paz Soldán, M. F. (1877). Diccionario Geográfico Estadístico del Perú. Imprenta del Estado.

Quilter, J. (2016). Magdalena de Cao y la arqueología colonial en el Perú. Boletín de Arqueología PUCP, 21, 69-83.

Raimondi, A. (1868). Viaje a Trujillo. Valle de Chicama – San Pedro de Guadalupe – Monsefú – Chiclayo – Lambayeque y Hacienda de Patapo (Fondo Antonio Raimondi). Archivo General de La Nación.

Raimondi, A. (1874). El Peru: Vol. Tomo I. Imprenta del Estado.

Raimondi, A. (1901). Itinerario de los viajes de Raimondi en el Perú. De Cajamarca a Hualgayoc-San Pablo-San Pedro-Talambo-Trujillo-Huanchaco-Chuquisongo-Cajabamba-Huamachuco-Cajamarquilla y Bambamarca (1860). Boletín de la Sociedad Geográfica de Lima, X, 1-40.

Reymundo, I. (2021). Contribución socioeconómica, política y cultural de extranjeros en la consolidación del sistema republicano en Trujillo (1820-1840) [Tesis de licenciatura]. Universidad Nacional de Trujillo.

Stappenbeck, R. (1929). Geologie des Chicamatales in Nordperu und seiner Anthrazitlagerstätten. Geologische und Palaeontologische Abhandlungen, 16(4): 305-355.

Stiglich, G. (1918). Derrotero de la Costa del Perú. Lit. y Tip . P. Berrio & Co . S. C.

Researchers , outstanding news