- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Visitor Regulations

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- The Salinar on the North Coast of Peru

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

PUCP Archaeology Students Visit the El Brujo Archaeological Complex ...

The Republican Settlements of El Brujo: Notes for the Recent History of Magdalena de Cao ...

To receive new news.

By: Yuriko Garcia Ortiz

The transition between the end of Cupisnique society and the beginning of the Moche on the north coast is unclear. At the end of the Formative Period (500 – 200 BCE), new historical scenarios of social and political reconfigurations arose following the decline of major ceremonial centers like Chavín de Huántar and other cults on the coast.

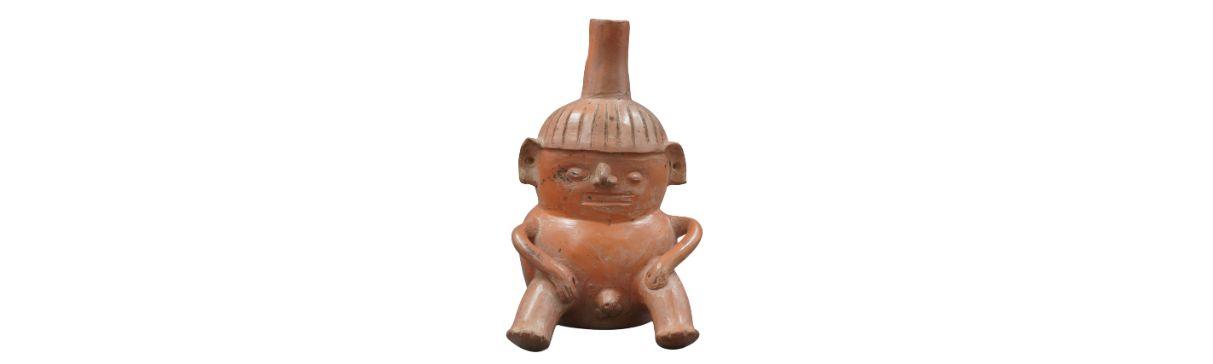

The “Salinar culture” (400 - 1 BCE), defined based on a large number of objects recovered from 228 funerary contexts in the middle Chicama Valley (Larco, 1944), is characterized by the emergence of local elites, greater social differentiation, and an increase in violence (Ikehara, 2019: 170-71; Kaulicke, 2010: 404-6). Populations preferred to inhabit small shelters located on the peaks of hills and valleys (Leonard and Russell, 1992: 23-26; Millaire, 2020; Russell et al., 1994: 189).

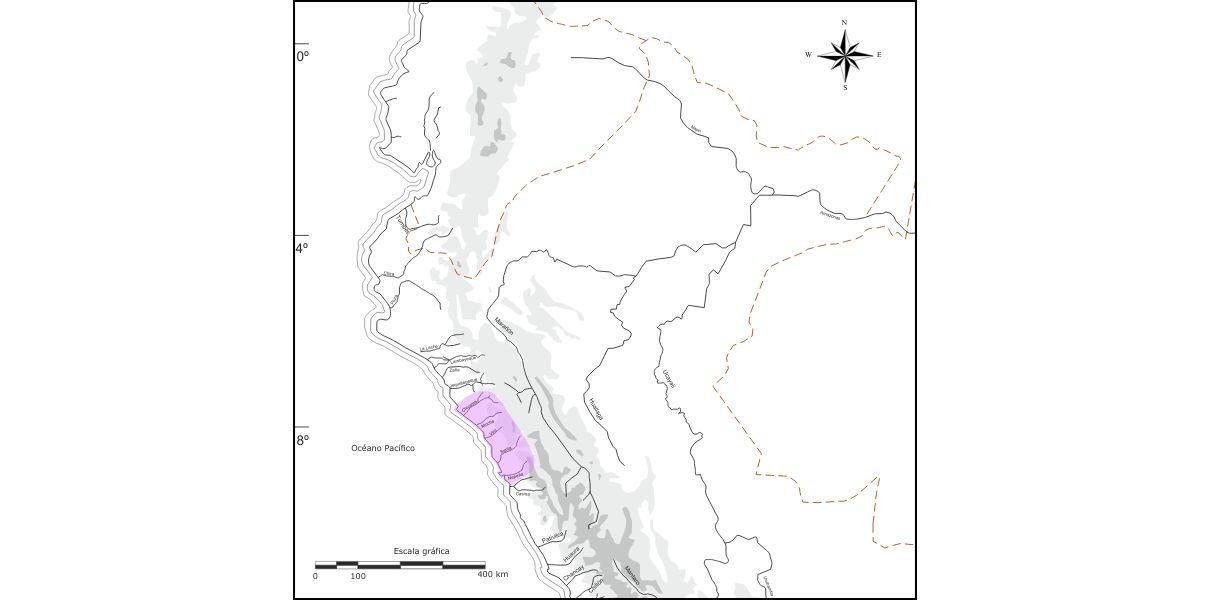

Spatial Distribution on the North Coast of Peru: Salinar Presence at El Brujo?

Although Salinar-style fragments have been reported at El Brujo, they appear mixed in some earthen fills associated with the Moche occupation (Quilter et al., 2012: 104). Therefore, lacking an architectural correlate indicating a tangible occupation of this site, we currently have a gap in the chronological sequence of the archaeological complex. However, new investigations will pave the way to clarify the human occupations in which Salinar ceramics and settlements were active on the north coast, as well as their particularities at El Brujo (Alva, 2024: 53).

In the Chicama Valley, the story is different. We can confirm the presence of Salinar elements from the north in Puémape, located in the Cupisnique Valley (Toshihara, 2004; Elera and Pinilla, 1992), as well as in Cerro Arena, located in the Moche Valley (Canziani, 2012).

From these findings, it has been interpreted that the populations of that time had a stratified social organization. Their settlements featured communal spaces dedicated to ritual events, administrative tasks, and economic activities, marking the beginning of an elite lifestyle (Ikehara and Chicoine, 2011: 156).

On the other hand, upon reevaluating the Nepeña Valley as a starting point for reviewing the Salinar phenomenon at the end of the Formative period on the Ancash coast, what is termed "Salinar" corresponds to a phenomenon implying a period of changes associated with increased inter-group conflicts and the development of a multitude of local trajectories sharing a series of social practices at the level of the Ancash coast and beyond on the north coast (Ikehara and Chicoine, 2011: 178).

Figure 1. Map of the distribution of Salinar archaeological evidence. Elaborated based on Ikehara and Chicoine (2011).

Visit El Brujo and Discover its 14,000 Years of History!

Schedule your visit to the El Brujo Archaeological Complex, check our opening hours and rates, and do not miss out on 14,000 years of history on the north coast of Peru.

References

Alva, J. (2024). La cerámica de El Brujo. Épocas Cupisnique y Mochica. Catálogo de Colección. Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Canziani, J. (2012). Ciudad y territorio en los Andes: Contribuciones a la historia del urbanismo prehispánico. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. Fondo Editorial.

Elera, C., & Pinilla, J. (1992). Bioindicadores zoológicos de eventos ENSO para el formativo medio y tardío de Puemape – Perú. In Resumenes Extendidos (pp. 93-97).

Ikehara, H. (2019). Formación de Economías de Gran Escala (500 a. C. - 500 d. C.). In P. Kaulicke (Ed.), Historia económica del antiguo Perú (pp. 156-257). Banco Central de Reserva del Perú - Instituto de Estudios Peruanos.

Ikehara, H., & Chicoine, D. (2011). Hacia una revaluación de Salinar desde la perspectiva del valle de Nepeña, costa de Ancash. Andes, 8, 153-184.

Kaulicke, P. (2010). Las cronologías del Formativo. 50 años de investigaciones japonesas en perspectiva (First edition). Fondo Editorial de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

Larco, R. (1944). Cultura Salinar. Síntesis monográfica. Sociedad Geográfica Americana.

Leonard, B., & Russell, G. (1992). Informe Preliminar: Proyecto de reconocimiento arqueológico del Chicama, resultados de la primera temporada de campo, 1989 (p. 192) [Unpublished report]. Instituto Nacional de Cultura.

Millaire, J. F. (2020). Dating the occupation of Cerro Arena: A defensive Salinar-phase settlement in the Moche Valley, Peru. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 57.

Quilter, J., Franco, R., Gálvez, C., Doonan, W., Gaither, C., Rosales, T., Jiménez, J., Starratt, H., & Koons, M. (2012). The Well and the Huaca: Ceremony, Chronology, and Culture Change at Huaca Cao Viejo, Chicama Valley, Peru. Andean Past, 10, 101-131.

Russell, G., Leonard, B., & Briceño, J. (1994). Cerro Mayal: Nuevos datos sobre la producción de cerámica Moche en el valle de Chicama. In S. Uceda & E. Mujica (Eds.), Moche: Propuestas y perspectivas (pp. 181-206). Institut français d’études andines.

Toshihara, K. (2004). El periodo Formativo en el valle de Chicama. In L. Valle (Ed.), Desarrollo Arqueológico de la Costa Norte del Perú (pp. 99-127).

Researchers , outstanding news