- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Visitor Regulations

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- The Cupisnique Era at El Brujo

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

PUCP Archaeology Students Visit the El Brujo Archaeological Complex ...

The Republican Settlements of El Brujo: Notes for the Recent History of Magdalena de Cao ...

To receive new news.

By: Yuriko Garcia Ortiz

Rafael Larco’s investigations (1941) in the Chicama Valley led to the identification of one of the earliest pre-Hispanic occupations in the La Libertad region. The material remains of this society were assigned the name Cupisnique, taken from the native toponym—apparently of Muchik origin—that names a gorge (quebrada) and hill located between the Jequetepeque and Chicama valleys (Campbell, 2000: 29; Chauchat et al., 2006: 3). Although the exact etymology of the term remains unknown due to the profound cultural transformation the north coast experienced during the Colonial period (Chauchat et al., 2006: 13), the use of the term persists today due to the importance of the reported archaeological vestiges.

Rafael Larco defined a "Cupisnique culture" for the first time based on ceramic styles associated with certain tombs and their iconographic affinity with the remains of monumental buildings made of conical adobes. Research suggests that during the Cupisnique era, the north coast underwent a period full of changes; populations diversified their diet and production with the introduction of irrigation agriculture, generating demographic growth. Furthermore, this period fostered the rise of monumental constructions of a religious nature and the utilization of various resources for other economic activities (Elera, 1993).

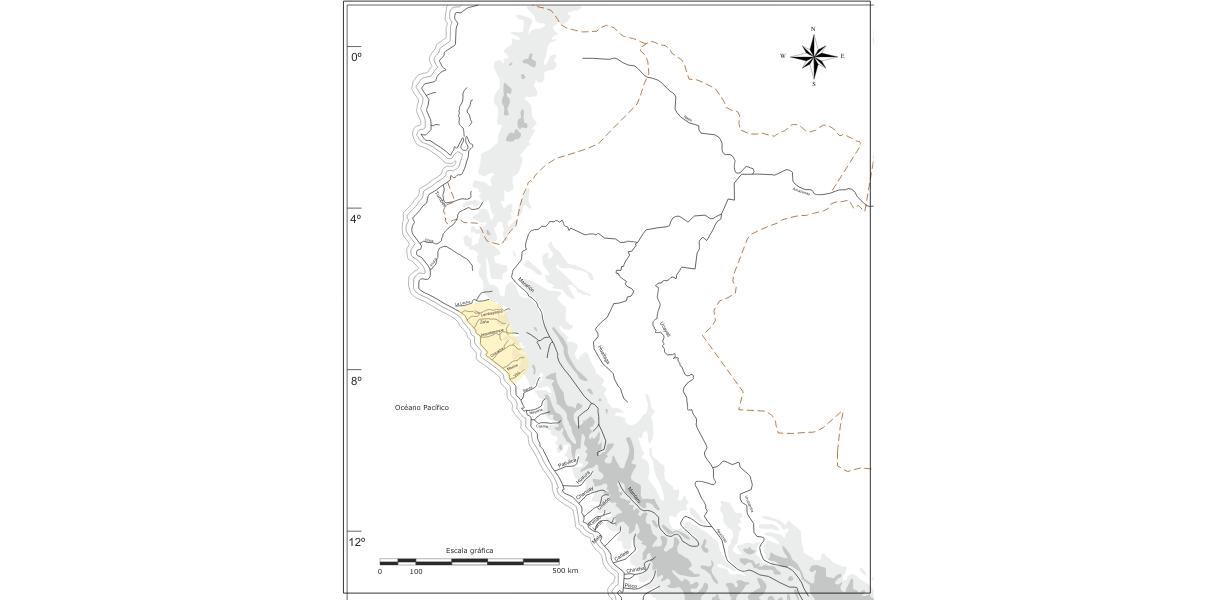

Figure 1. Cupisnique Region in La Libertad (Chauchat et al., 2006: 4).

Stylistic Definition, Decoration, and Construction System

Larco established the first cultural sequence for the Formative Period on the north coast of Peru (1700 - 200 BCE) based on the identification and ordering of ceramic styles found in the La Libertad region (Larco 1941: 34-46). He recorded the first forms of stirrup spouts (asa estribo) in the Cupisnique tradition (Larco, 1948: 18), characterized by closed-kiln firing which gives them a dark, blackish color (monochrome).

From this assemblage, Larco (1948: 17) defines four types of stirrup spouts: (a) Thick handles with a short spout and divergent rim. (b) Almost triangular handles, with a long, straight spout. (c) Flattened handles, more or less triangular with a divergent bell-shaped spout. (d) Round handles with a short and slightly bulging spout, with prominent and convergent rims.

Associated with these types are various forms of bottles, ranging from globular to cylindrical, featuring incised decoration and zoomorphic, geometric, and phytomorphic motifs (Larco, 1941: 34).

Figure 2. Types of Cupisnique ceramic stirrup spouts. CAEB pieces: EBBCE00000-190 and EBBCE00000-1. Larco Museum pieces: ML015082 and ML010863.

The second ceramic assemblage, towards the end of the Middle Formative (1200 - 700 BCE), is termed Transitional Cupisnique. It presents greater diversity in forms, decorative elements, reddish or light brown colors alongside black (bichrome), and the consistency of finishing techniques (burnishing and polishing).

Regarding architecture, two types of raw materials were recognized in the Cupisnique construction system: stone and conical adobes. Constructions using stone are recurrent in Pampa de los Fósiles, as well as those reported on the road to Mocán and similar to Sausal, Barbacoa, and Palenque in the Chicama Valley (Larco, 1941: 115). Furthermore, at some sites like Barbacoa, the use of both materials is frequent, primarily for funerary architecture constructions (Larco, 1941: 116). On the other hand, with the introduction of adobe, mastery of wall plastering was also acquired (Larco, 1941: 117); the use of this construction material is recorded at Huaca Pucuche in the Chicama Valley, in the thick walls within Hacienda Salamanca (Pacasmayo Valley), and other locations near Cupisnique.

Figure 3. Conical adobes from Huaca Pucuche and the wall of Hacienda Salamanca (Larco, 1941: 122).

Regarding the subsistence pattern, the agricultural diet was supplemented with marine resources during the Cupisnique era. Thus, protein supplements were utilized through exchange systems, as reported at the site of Gramalote, located on the Huanchaco coast, and at Huaca Los Reyes in the Moche Valley, suggesting active transit between the coast and the interior of the valleys to complement their economies (Campbell, 2000: 28).

Territorial Distribution on the North Coast and Chronology

Archaeological evidence related to Cupisnique during the Middle Formative period (1200 - 700 BCE) is found in a territory spanning the regions of Lambayeque and La Libertad (Kaulicke, 2008). According to Larco, the materialization of the feline cult, widespread in Cupisnique society, is ideologically manifested in architecture and ceramics (Sakai and Martinez, 2014: 226) during a period of certain social and political autonomy (Nesbitt, 2012).

The most representative archaeological sites of the Archaic period that define these processes of continuity and change toward the Formative in the Lambayeque Valley are Collud-Zarpán, Arenal, and Ventarrón (Alva, 2008: 113). Similarly, in the Jequetepeque Valley, sites such as Limoncarro, Huaca Cerro La Cal, Huaca Laguna, Huaca Petaique, Huaca Cerro Pa-Ñi, Huaca Cultambo, Huaca Marín, and Huaca Herrera present platform-type structures with walls built of conical adobe (Sakai and Martinez, 2014: 234).

In the Chicama Valley, Puemapé (Elera, 1998) and Huaca Prieta (Bird et al., 1985) located near the coast, and the valley huacas: Huaca Pucuche, Facalá, Cruz La Botija, the cemeteries in the former haciendas Sausal and Casa Grande, and the set of sites recorded by Chauchat (Toshihara, 2002: 155) are characterized by their buildings made of river stones (cantos rodados), adobes, and burials of individuals with pathologies and fractures.

Toward the Moche Valley, the situation is more dispersed; the Caballo Muerto complex and other early sites such as Gramalote or Menocucho (Toshihara, 2002: 174-7), as well as Huaca El Gallo in the Virú Valley (Toshihara, 2002: 181), can be mentioned.

Figure 4. Map with the most representative sites of the Middle Formative on the north coast. Created based on Alva (2024: 31).

Cupisnique Burials at El Brujo

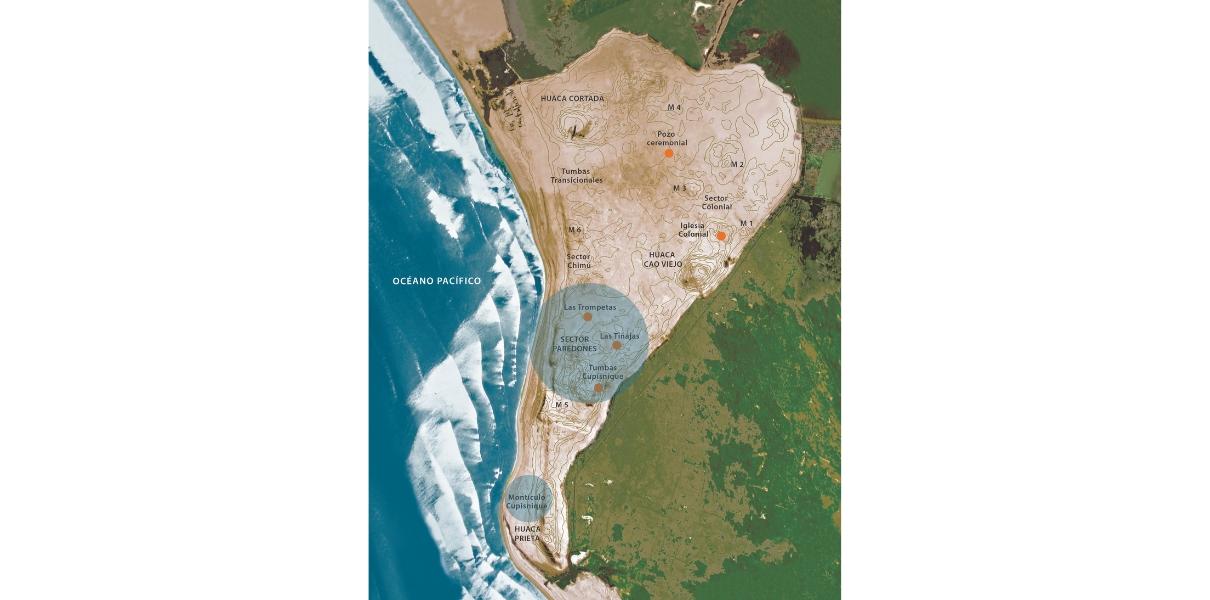

Between 1996 and 1997, domestic contexts were recorded at the Cupisnique Mound, located north of Huaca Prieta, along with funerary contexts in the Paredones sector (Franco et al., 1997: 88-96). These spaces allowed for the examination of architectural construction models, raw materials, grave goods, and the individuals who lived at El Brujo during the Formative period.

Figure 5. Cupisnique sectors at the CAEB. Created based on Mujica (2007).

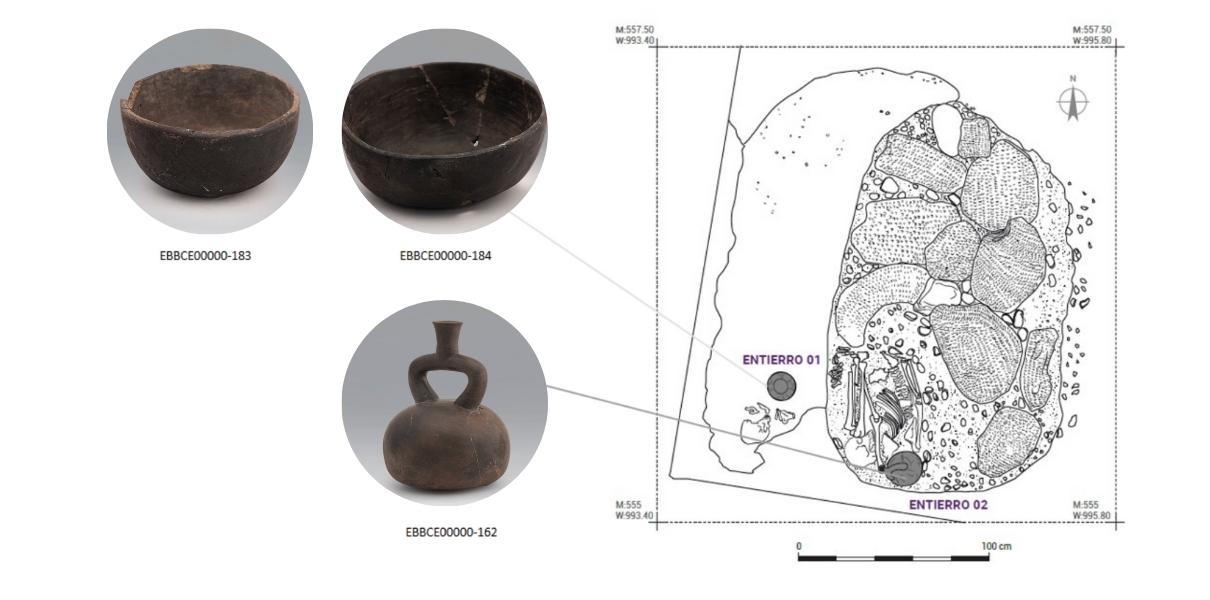

In the funerary contexts of the Paredones sector, 6 burials associated with Cupisnique material were recorded. From these findings, a series of pathologies identified in the individuals shed light on the subsistence pattern at El Brujo. For instance, the absence of cavities and secondary abscesses due to the lack of a diet rich in carbohydrates and soft foods (Franco et al., 1997: 114-5), and the irritation of the ear canal in Burial 01, suggest continuous exposure to cold water caused by relying on marine resources for their diet (Mujica, 2007: 71). These individuals utilized shellfish gathering of species such as Donax sp., Semimytilus algoses, Prisogaster niger, Xanthochorus buxeus, Thais chocolata, Tegula atra, and Mitra orientalis, in addition to fishing, with anchovy being the most abundant species (Campbell, 2000: 76).

Figure 6. Cupisnique Burials 01 and 02. (Alva, 2024: 71-2).

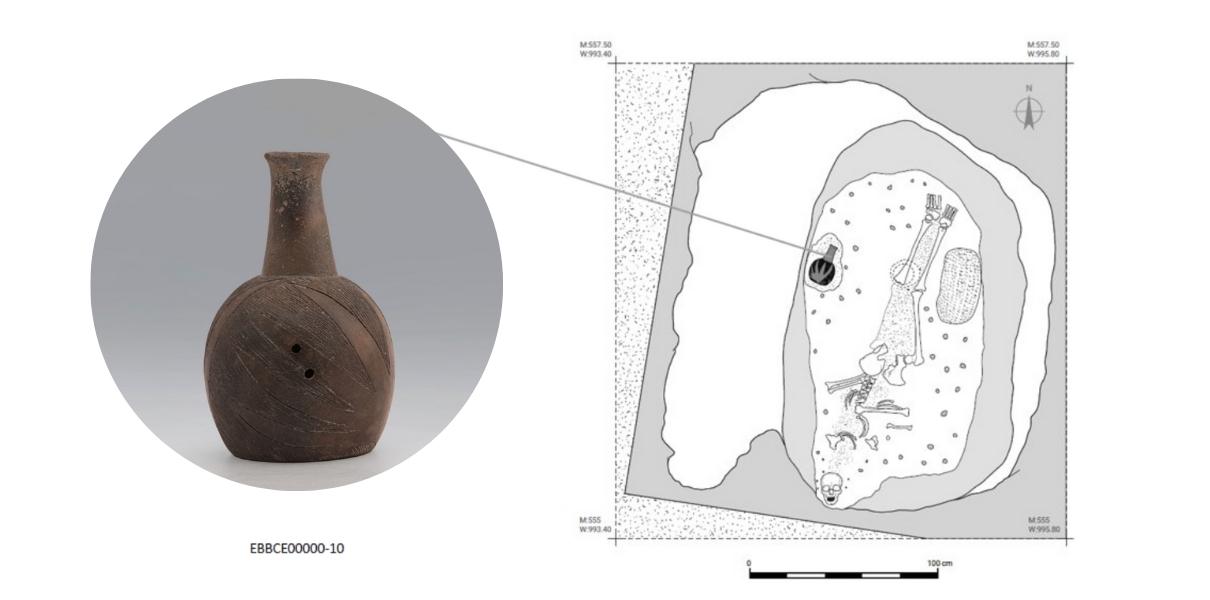

On the other hand, accompanying the male individual in Burial 03 of Paredones, a closed-kiln fired vessel (EBBCE00000-10) was found. It was decorated with thick, deep incised lines forming figures resembling two six-pointed leaves arranged on both sides of the piece. The exterior of the figures was carefully filled with fine incised lines, possibly using an instrument with several thin points (Alva, 2024: 285).

Figure 7. Cupisnique Burials [Context of Burial 03]. (Alva, 2024: 71-2).

Additionally, among the objects found in Burial 03, carved bone pieces representing feline characters with traces of red and black paint were recorded.

Do you want to know more about the Cupisnique? Request our specialized route and complement your visit to Huaca Cao Viejo with the ancient Huaca Prieta and the monumental Huaca Cortada!

References

Alva, I. (2008). Los complejos de Cerro Ventarrón y Collud-Zarpán: Del Precerámico al Formativo en el valle de Lambayeque. Boletín de Arqueología PUCP, 97-117.

Alva, J. (2024). La cerámica de El Brujo. Épocas Cupisnique y Mochica. Catálogo de Colección. Fundación Wiese.

Bird, J., Hyslop, J., & Dimitrijevic, M. (1985). The preceramic excavations at the Huaca Prieta, Chicama Valley, Peru. Vol. 62, part 1. New York: American Museum of Natural History.

Campbell, K. (2000). Fauna, subsistence patterns and complex society [Master's Thesis]. Northern Arizona University.

Chauchat, C., Wing, E., Lacombe, J.-P., Demars, P.-Y., Uceda, S., & Deza, C. (2006). Prehistoria de la costa norte del Perú: El Paijanense de Cupisnique. In Prehistoria de la costa norte del Perú: El Paijanense de Cupisnique. Institut français d’études andines.

Elera, C. (1993). El Complejo Cultural Cupisnique: Antecedentes y Desarrollo de su Ideología Religiosa. SENRI Ethnological Studies, 37, 229-257.

Franco, R., Gálvez, C., & Vásquez, S. (1997). Programa Arqueológico Complejo «El Brujo». Informe Final Temporada 1997. Magdalena de Cao: Fundación Wiese, Instituto Nacional de Cultura - La Libertad, Universidad Nacional de Trujillo.

Kaulicke, P. (2008). La economía en el periodo Formativo. In C. Contreras (Ed.), Compendio de historia económica del Perú, tomo 1: Economía prehispánica (pp. 137-219). Banco Central de Reserva del Perú: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos.

Larco, R. (1941). Los Cupisniques. Sociedad Geográfica de Lima.

Larco, R. (1948). Cronología Arqueológica del Norte del Perú. Sociedad Geográfica de Lima.

Mujica, E. (ed). (2007). El Brujo: Huaca Cao, centro ceremonial Moche en el Valle de Chicama. Lima, Fundación Wiese.

Nesbitt, J. (2012) Excavations at Caballo Muerto: An Investigation into the Origins of the Cupisnique Culture. [Unpublished PhD Dissertation], Yale University.

Sakai, M., & Martínez, J. (2014). Repensando Cupisnique: Organización social segmentaria y arquitectura zoo-antropomorfa en los centros ceremoniales del valle bajo del Jequetepeque durante el Período Formativo Medio. SENRI ETHNOLOGICAL STUDIES, 89, 225-243.

Toshihara, K. (2002). The Cupisnique Culture in the Formative Period world of the Central Andes, Peru [Doctoral Thesis]. University of Illinois.

Researchers , outstanding news