- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Visitor Regulations

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- Virú-Gallinazo at El Brujo

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

PUCP Archaeology Students Visit the El Brujo Archaeological Complex ...

The Republican Settlements of El Brujo: Notes for the Recent History of Magdalena de Cao ...

To receive new news.

By: Yuriko Garcia Ortiz

Traditionally, Virú-Gallinazo is known as an archaeological culture whose chronological location corresponds to the beginning of the Early Intermediate Period (200 BCE – 600 CE) on the north coast of Peru. Its definition took place around 1933, when Rafael Larco adopted the name Virú, the valley adjacent to Moche, as the eponym for a "culture" characterized by the use of vessels decorated with negative painting (a decorative technique achieved by differentiated smoking of the containers). These were initially found at Pampa de Cocos (Moche Valley) and at the Castillo de Tomaval (Virú Valley) (Bennett, 1950: 17). For Larco, the technological characteristics of the decoration showed affinities with the pottery of the Callejón de Huaylas (Larco, 1945: 1-3).

The investigations of Wendell Bennett in the lower Virú Valley, initially developed in 1936 and continued in 1946 (Bennett, 1950), named that same style of negative decoration as Gallinazo. This denomination came from the local name of site V-59, considered the "type site" where the ceramic style was widely reported. Furthermore, Gallinazo was a distinctive name that avoided confusion regarding cultural assignments in the Virú Valley (Bennett, 1950: 15-19).

Although other researchers debate the use of each term and lean toward one or the other (Cf. Donnan, 1973), at the El Brujo Archaeological Complex, we recognize both denominations (Virú-Gallinazo) to refer, for the moment, to ceramic assemblages whose production and use occurred in the first centuries of our era. These vessels had their beginnings in a period prior to the emergence of monumental buildings and the Moche style, associating them with extensive settlements of agglutinated enclosures located in the lower and middle parts of the northern valleys.

Wendell Bennett and the Virú Project

The Virú Project was executed in 1946. Its results were shared at the Chiclín round table of that year (Ramón, 2005: 11). Based on Bennett's previous work in 1936 (Bennett, 1939), the Virú Project aimed to elaborate a cultural synthesis based on the compilation and analysis of data (organized into ceramic typologies) obtained from surveys and multiple archaeological excavations carried out at specific sites in the valley (Bennett, 1950: 6).

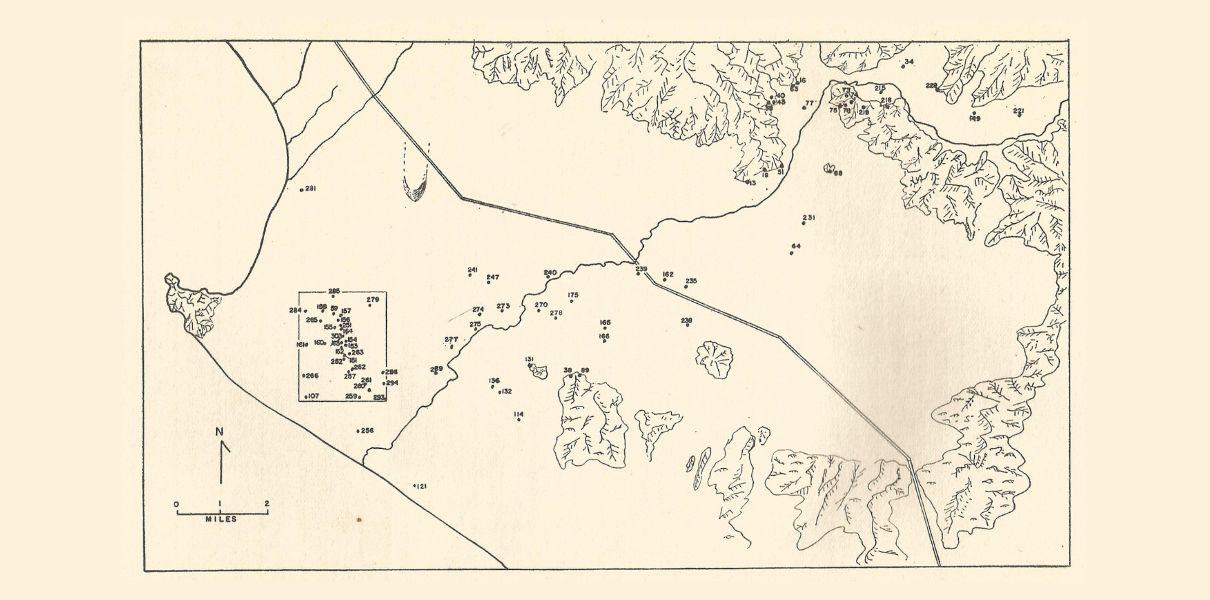

The term "Gallinazo Group" was given to the set of 30 sites with Gallinazo stylistic affiliation, located near the mouth of the Virú River at the Pacific Ocean (Bennett, 1950: 19).

Figure 1. Map of the sites of the Virú Valley Project: numbering indicates each site with Gallinazo occupation, and the rectangle indicates the sites of the “Gallinazo Group” (Bennett, 1950: 15).

Virú-Gallinazo: What do we know about its distribution on the north coast of Peru?

Given the emphasis of research, it is currently considered that the nuclear territory of a "Virú-Gallinazo culture" was the Virú Valley, located 50 km south of the city of Trujillo. The utilization of valleys and irrigation canals to feed cultivation fields drove the distribution and construction of sites near the river.

From an eminently stylistic perspective, Rafael Larco defines two periods for the Gallinazo: a peak era, where Virú-Gallinazo ceramics coexisted with the initial phases of the Moche style; and a decadent era that survived until Tiahuanaco domination (Larco 1945: 1).

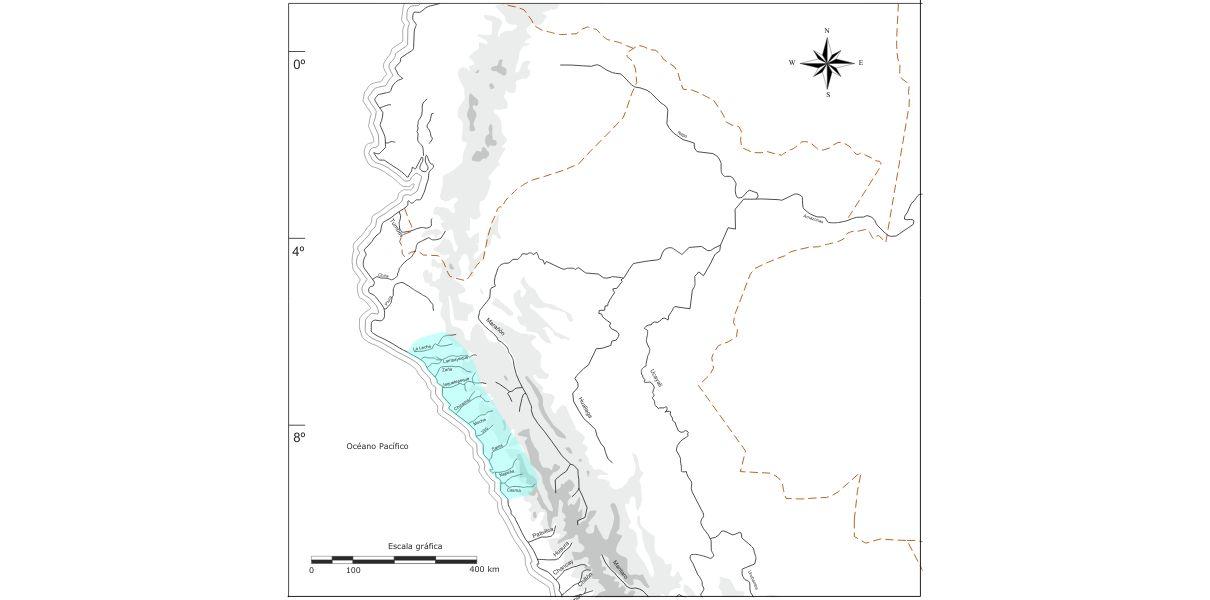

Current studies show that the spatial and temporal distribution of Virú-Gallinazo styles on the north coast of Peru turned out to be wider than originally proposed. Investigations have recorded the presence of archaeological evidence attributable to Virú-Gallinazo to the north of the La Libertad region in the valleys of La Leche, Lambayeque, Zaña, and Jequetepeque (Shimada, 1994: table 1.2), while to the south, vestiges found in the valleys of Santa, Nepeña, and Casma are discussed (Shimada, 1994).

Figure 2. Map of the distribution of Virú-Gallinazo archaeological evidence. Elaborated based on Shimada (1994).

Stylistic Definition of Ceramic Vessels and Architecture

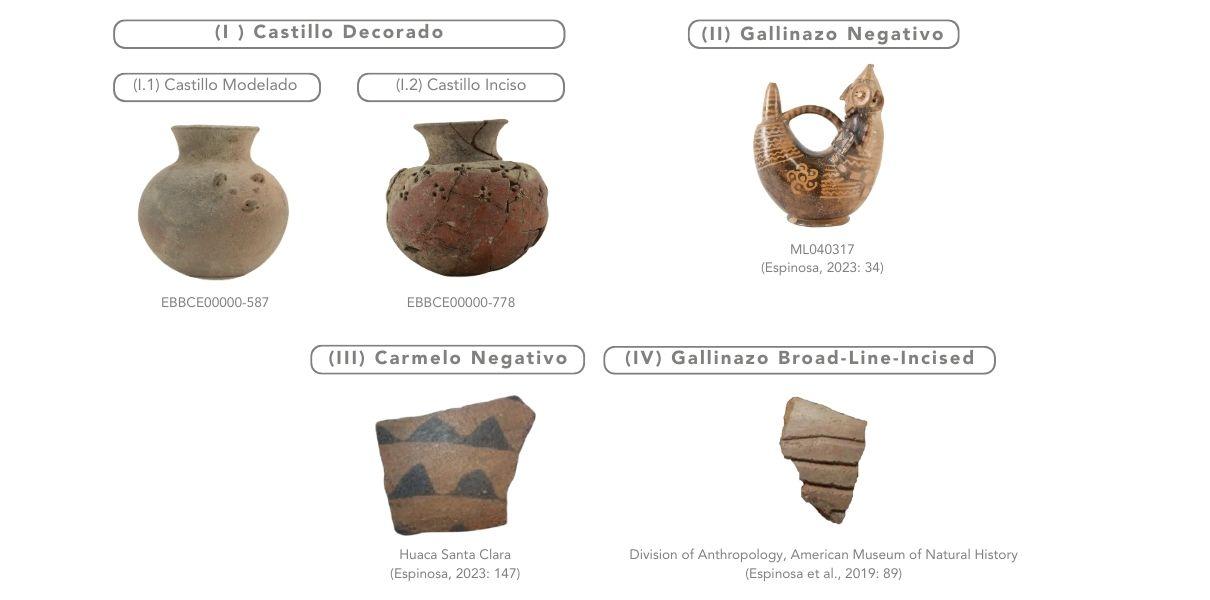

With the objective of understanding the occupational sequence of the Virú Valley, in the 1940s a relative chronology was proposed based on changes in ceramic types within stratigraphy (Espinosa et al., 2019: 87). In these studies, ceramics akin to Virú-Gallinazo were classified into five types (Ford, 1949: 63-65): (a) Castillo Decorated (with its variants Castillo Modeled and Castillo Incised; (b) Gallinazo Negative; (c) Carmelo Negative and (d) Gallinazo Broad-Line-Incised (Espinosa et al., 2019: 88). This classification continues to be used for the archaeological study of pottery productions and chronological definitions.

Figure 3. Virú-Gallinazo ceramic types. The Castillo Decorated samples are from the CAEB.

On the other hand, the Gallinazo architectural pattern in the Virú Valley was associated with architectural superimposition, the type of construction material, and ceramics. Thus, Bennett (1950) subdivides the Gallinazo occupation into three phases: Gallinazo 1: Features constructions in tapia (rammed earth), with walls decorated with geometric motifs (Ibid. 65-67); Gallinazo 2: Characterized by a construction pattern of honeycomb-shaped rooms transitioning to rectangular and quadrangular rooms, using hemispherical, rounded, and flat adobe bricks (Ibid., 67) and Gallinazo 3: Receives influences from societies foreign to the Virú Valley (Moche and Recuay); therefore, cane-mold marked adobes and monumental constructions are recorded (Ibid., 68-69).

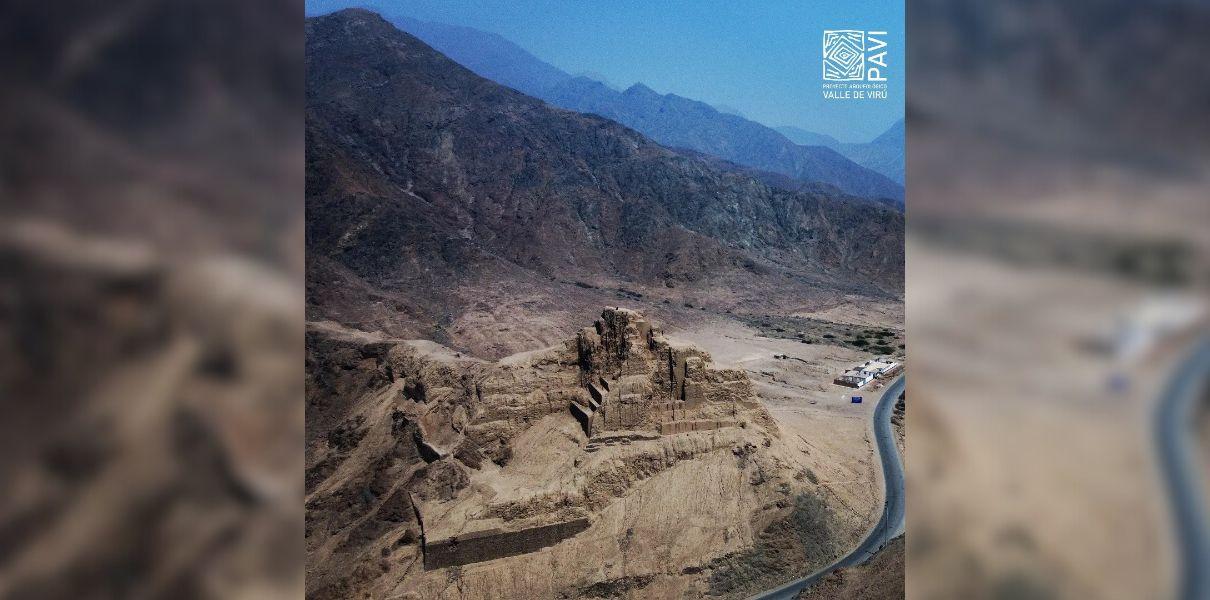

The entry of Moche objects marks a substantial change in Virú-Gallinazo production. The consolidation of Moche power on the north coast is characterized by the massive use of adobe for the construction of monumental buildings, which revitalized the formation of civic-ceremonial centers (Shimada, 1994: 35; Alva, 2024).

Figure 4. Castillo de Tomabal. Photography: Virú Valley Archaeological Project.

Contexts with Virú-Gallinazo Evidence at El Brujo

At the El Brujo Archaeological Complex, the vessels reported in different sectors are found mostly in tombs and contexts of a public-ceremonial nature (Alva, 2024: 54). For this reason, they present finer decoration intended for elite consumption and ritual paraphernalia.

At the foot of Huaca Prieta, Junius Bird excavated a large jar and mud deposits associated with dry agricultural products and Virú-Gallinazo ceramic material (Bird et al. 1985: 26-27). Recent dating of these contexts indicates an age between 100 BCE and 380 CE (Millaire et al. 2016: E6019), times prior to the initial construction stages of Huaca Cao Viejo.

In Huaca Cao Viejo, the set of elite burial contexts in the northwest enclosure records Virú-Gallinazo style vessels accompanying Moche contexts among the offerings in the tomb of the Lady of Cao, as well as in tomb 01 of the Main Priest.

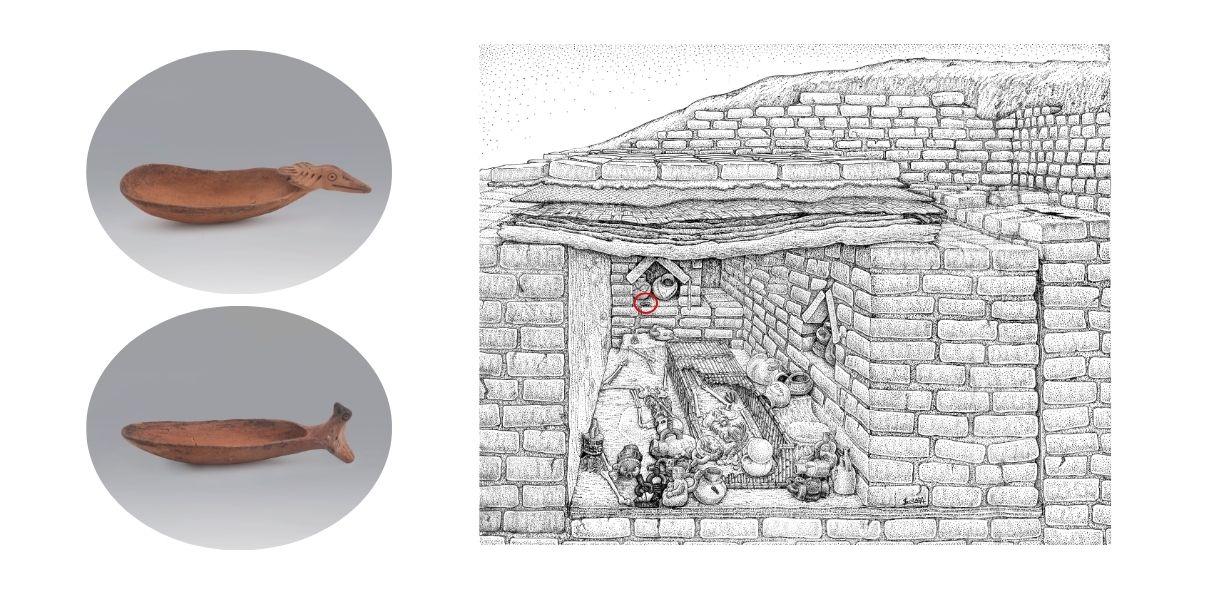

Similarly, in the intrusive contexts of the upper platform of Cao Viejo, we found one of the most complex archaeological burials, as it contains at least two funerary events within it (Franco et al., 1998). Tombs 01 A and B are defined by an adobe chamber conditioned between the BATs (Large Adobe Blocks) that served as foundations for the third building. In this space, in the chamber of tomb 01 B, 35 ceramic vessels were found, including 2 spoons whose bodies present modeled appendages in the form of birds with Virú-Gallinazo cultural affiliation (Alva, 2024: 132-141).

Figure 5. Recreation of tomb 01B, view from south to north. Drawing: Segundo Lozada (Alva, 2024: 151) and Virú-Gallinazo spoons (Alva, 2024: 308-11).

Explore Our Collections

Access the El Brujo catalog and enjoy the repository of pieces exhibited in the Cao Museum. Additionally, with our collection catalog "The Ceramics of El Brujo. Cupisnique and Moche Epochs," you can learn more about the pre-Hispanic societies that inhabited the Chicama Valley.

References

Alva, J. (2024). La cerámica de El Brujo. Épocas Cupisnique y Mochica. Catálogo de Colección. Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Bennett, W. (1939). Archaeology of the North Coast of Peru. An Account of Exploration and Excavation in Viru and Lambayeque Valleys (Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History, Volume XXXVII, Part I). The American Museum of Natural History.

Bennett, W. (1950). The Gallinazo Group. Viru Valley, Peru. Yale University Press.

Bird, J., Hyslop, J. y Dimitrijevic, M. (1985). The preceramic excavations at the Huaca Prieta, Chicama Valley, Peru. Vol. 62, part 1. New York: American Museum of Natural History.

Donnan, C. B. (1973). Moche occupation of the Santa Valley, Perú. University of California of publications in the Anthropology. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Espinosa, A. (2023). Filiaciones culturales y contactos entre las poblaciones Virú-Gallinazo y Mochica (200 AC – 600 DC, costa norte del Perú). Archaeopress Publishing Ltd.

Espinosa, A., Prieto, G., & Alva, W. (2019). Tradiciones técnicas y producción cerámica virú-gallinazo y mochica: Nuevas miradas sobre las relaciones entre dos grupos sociales del Período Intermedio Temprano en la Costa Norte del Perú. Boletín de Arqueología PUCP, 0(26).

Franco, R., Gálvez, C., & Vásquez, S. (1998). Programa Arqueológico Complejo «El Brujo». Informe Final Temporada 1998 (p. 139). Fundación Wiese, Instituto Nacional de Cultura - La Libertad, Universidad Nacional de Trujillo.

Larco, R. (1945). La cultura Virú. Sociedad Geografica Americana.

Ramón Joffré, G. (2005). Periodificación en arqueología peruana: genealogía y aporía. Bulletin de l'Institut français d'études andines, 34(1), 5-33.

Shimada, I., & Maguiña, A. (1994). Nueva visión sobre la cultura Gallinazo y su relación con la cultura Moche. En S. Uceda & E. Mujica (Eds.), Moche: Propuestas y Perspectivas (pp. 31-58). Universidad Nacional de La Libertad -Trujillo.

Researchers , outstanding news