- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Visitor Regulations

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- Trades in Colonial Magdalena de Cao

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

PUCP Archaeology Students Visit the El Brujo Archaeological Complex ...

The Republican Settlements of El Brujo: Notes for the Recent History of Magdalena de Cao ...

To receive new news.

By: Yuriko Garcia Ortiz

Trades after the conquest responded to the economic needs of the time. These activities were carried out by men and women from different social groups, all under the framework of the colonial economy controlled by the Spanish Crown.

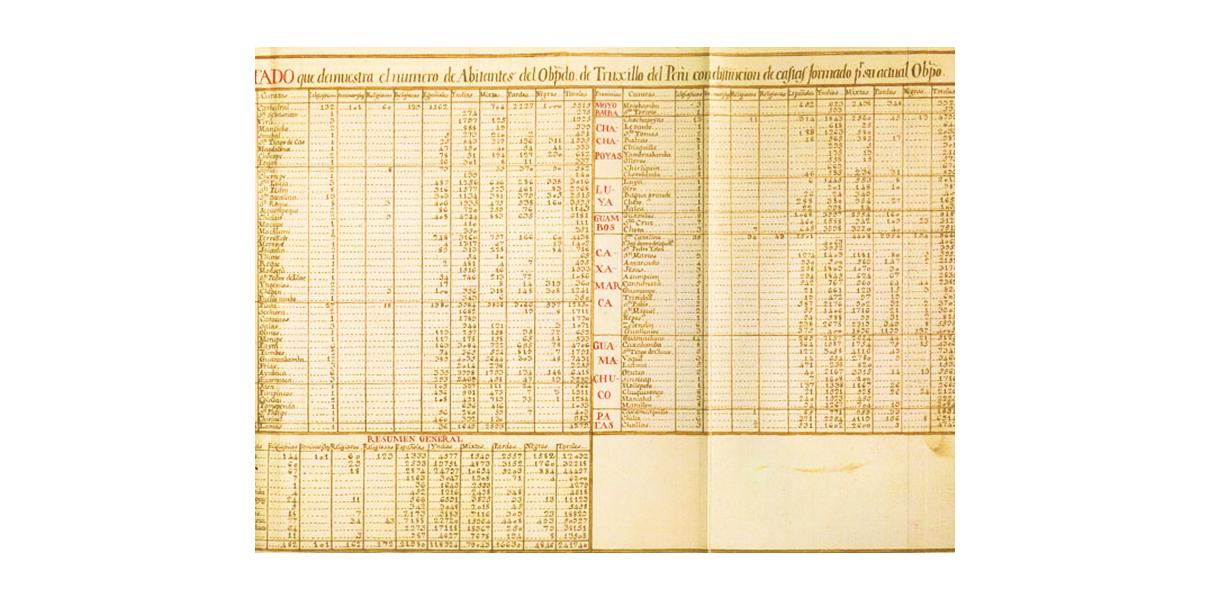

The city of Trujillo was the center of colonial life on the northern coast during the thirty years following the conquest (Ramírez, 2016 in Aljovín de Losada & Aljovín de Losada, 1998: 243). In addition to being one of the first cities founded by the Spanish during the Viceroyalty of Peru (Quesada, 2013: 24), the valleys and Indian reducciones provided the labor force for agricultural, livestock, and artisanal production to supply the city.

What trades existed during the colonial period?

Specializing in an activity meant practicing a trade, becoming part of social practices, and contributing to the economy of the time. While Peru’s artisanal history was strongly linked to textiles, there was also an important sector dedicated to producing sugar, soap, glass, liquor, clothing, metals, and more.

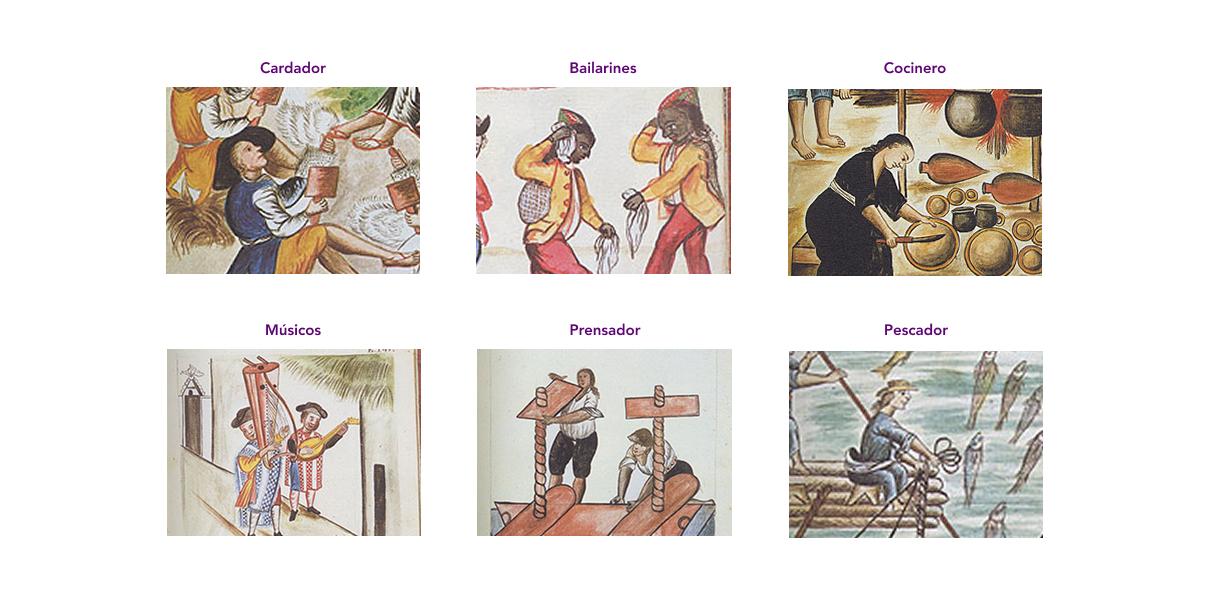

Trades were divided into two main groups:

- Those devoted to the production of movable and immovable goods.

- Those offering services such as barbers, musicians, or singers.

Table 1. List of trades for the production of movable goods during the early colonial period (based on Salas, 2020: 447).

In the jurisdiction of Trujillo, ordinances began to take effect in the second half of the 16th century (Meseldzic, 1993: 80). These ordinances regulated how trades were organized, the types that could be practiced, and the training of new apprentices. In the case of shoemakers in Trujillo, this trade was significant because it embodied both necessity and prestige (Meseldzic, 1993: 83). Indigenous artisans stood out as shoemakers thanks to their quick learning skills, working alongside tanners who provided raw materials such as leather, sheepskin, and gilded leathers (guadamecíes) (Castañeda, 2019).

Apprentices, journeymen, and masters: Who could practice these activities?

In early colonial times, restrictions were imposed on the practice of various trades both in Lima and in the provinces. The first Spanish masters and artisans began to incorporate Indigenous people into their work, and in many cases, also their African slaves (Meseldzic, 1993: 65).

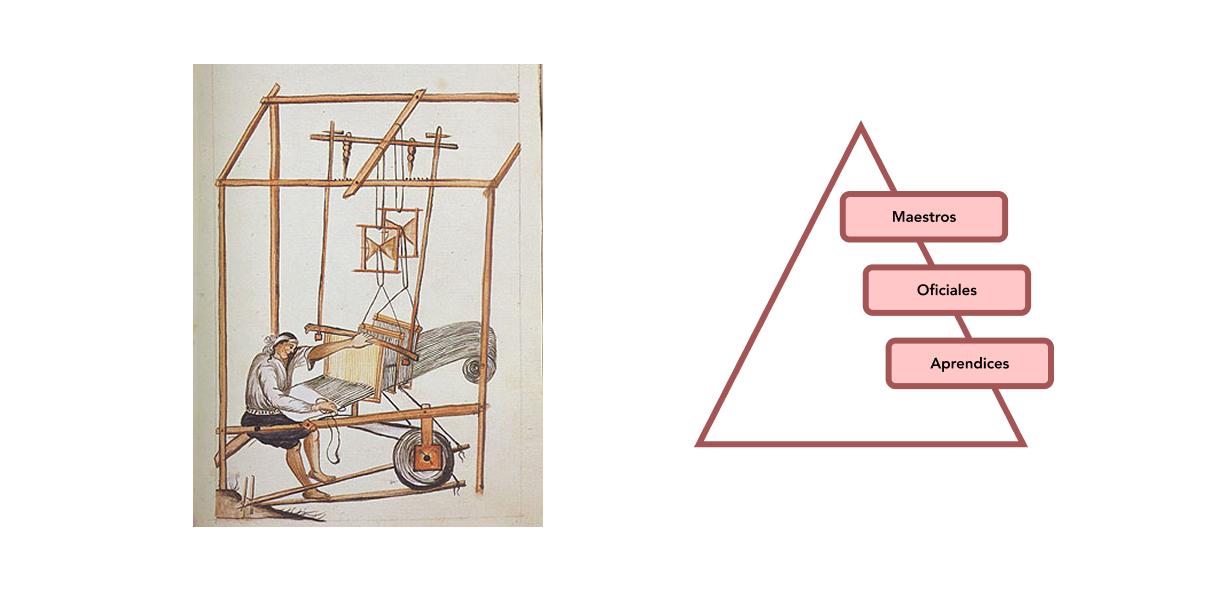

The artisanal landscape was structured as follows:

- Masters: specialists from the Iberian Peninsula who owned their own workshops, produced and sold goods, and were authorized to train others.

- Journeymen: recently trained workers who could practice the trade under a master (Gómez, 2005).

- Apprentices: youths admitted to learn the trade, in limited numbers to avoid oversupply. Masters were responsible for their food and clothing (Quesada, 2013: 136; Meseldzic, 1993: 66; Galino, 1962).

In Trujillo, much of the Afro-descendant population was enslaved, dedicated mainly to domestic service. However, a group managed to learn trades and rise to positions as journeymen and master bakers, chair makers, shoemakers, button makers, masons, carpenters, blacksmiths, guitar makers, and stonecutters (Castañeda, 1996: 166). Like Indigenous people, their skills allowed them to integrate into the colonial economy, working also as shopkeepers (pulperos), domestic servants in Spanish households, and muleteers transporting goods to Lima, Piura, or the northern highlands (Castañeda, 1996: 166).

Archaeological pieces from El Brujo: tools and trades inferred

The storerooms of the El Brujo Archaeological Complex safeguard approximately 11,000 pieces, many of which allow us to infer the trades required for their production.

Findings point to colonial textile production: from spinning and dyeing sheep’s wool, to pressing for felt-making, to tailoring Spanish-style garments (Brezine, 2020). Other objects, such as metal artifacts, reveal the work of blacksmiths in creating jewelry, Christian crosses, and iron railings for church plazas (Quilter & Franco, 2020).

Visit the El Brujo Archaeological Complex!

Along the main visitor route, you can explore the remains of colonial occupation in the ancient town of Magdalena de Cao. In addition, Room 2 of the Cao Museum displays evidence of these economic activities.

References

Aljovín de Losada, P., y Aljovín de Losada, C. (1998). La élite noble de Trujillo de 1700 a 1830. En S. O'Phelan Godoy e Y. Saint-Geours (Eds.), El norte en la historia regional, siglos XVIII y XIX (pp. 241-293). Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos.

Brezine, C. (2020). Textiles y vestimenta. En J. Quilter (Ed.), Magdalena de Cao. Un pueblo colonial temprano en la costa norte del Perú (pp. 163–188). Prensa del Museo Peabody.

Castañeda, J. (1996). Notas para una Historia de la Ciudad de Trujillo del Perú en el Siglo XVII. En H. Tomoeda & L. Millones (Eds.), La tradición andina en tiempos modernos (pp. 159-189).

Castañeda, J. (2019). La ocupación indígena de la traza urbana de la ciudad de Trujillo [Tesis de maestría inédita]. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

Gaither, C. y Murphy, M. (2020). Bioarqueología. En J. Quilter (Ed.), Magdalena de Cao. Un pueblo colonial temprano en la costa norte del Perú (pp. 107–146). Peabody Museum Press.

Galino, M. Á. (1962). El aprendiz en los gremios medievales. Revista Española de Pedagogía, 20(78), 117-130.

Gómez, C. (2005). Maestros, oficiales y aprendices. Notas sobre el mundo artesanal en Albacete en la segunda mitad del siglo XVIII. Revista de estudios Albacetenses, 49, 161-190.

Martínez Compañón, B. J. (1985). Trujillo del Perú: Vol. II (Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional).

Martínez Compañón, B. J. (1985). Trujillo del Perú: Vol. I (Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional).

Meseldzic, Z. (1993). Pieles y cueros del Perú Virreynal. Sociedad Geográfica de Lima.

Quesada, A. (2013). Del comer y el beber. Cultura alimentaria en la ciudad de Trujillo (1600 – 1720) [Tesis de licenciatura]. Universidad Nacional de Trujillo.

Quilter, J. y Franco, R. (2020). Panorama del proyecto de investigación. En J. Quilter (Ed.), Magdalena de Cao. Un pueblo colonial temprano en la costa norte del Perú (pp. 23–76). Peabody Museum Press.

Ramírez, S. (2016). Tierra y tenencia en el Perú colonial temprano: Individualizando a los sapci, «Lo que es común a todos». The Medieval Globe, 2(2), 33-71.

Salas, M. (2020). Manufacturas y precios en el Perú colonial, la producción textil y el mercado interno, siglos XVI y XVII. En C. Contreras (Ed.), Compendio de historia económica del Perú. Economía del periodo Colonial Temprano (pp. 447-531). BCRP, IEP.

Researchers , outstanding news