- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Visitor Regulations

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- New Livestock Species During the Colonial Period at El Brujo

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

PUCP Archaeology Students Visit the El Brujo Archaeological Complex ...

The Republican Settlements of El Brujo: Notes for the Recent History of Magdalena de Cao ...

To receive new news.

By: Yuriko Garcia Ortiz

The Spanish conquest generated a deep socioeconomic transformation in the Americas, evidenced by the introduction of new animal and plant species. With the arrival of Europeans, horses, pigs, sheep, goats, chickens, and other animals were introducedi, which changed Indigenous agricultural and herding practices and laid the foundations of the colonial economy.

Intended mainly to meet the dietary habits of European settlers and speed up their mobility across the territory, records for Mexico and Peru show that the first animals introduced were horses and pigs, the latter favored for their rapid reproduction (Tateischi, 1940; Alcalá, 2000: 660 in Lefebvre and Manin, 2019). In this way, with the arrival of the new species, Indigenous populations diversified their diet and their access to inputs for production (Lefebvre and Manin, 2019: 57).

Livestock introduced in the city of Trujillo

The colonial economy in northern Peru favored cities with fertile valleys and port access, making them obligatory stops on trade routes. Thus, thousands of head of large and small livestock were introduced and placed under the care of Indigenous and Afro-descendant people (Contreras and Hernández, 2017). Livestock played a relevant role and was used as pack animals, sources of food, and for other by-products (Salazar-Soler, 2020; Iniesta et al., 2020). In this way, a considerable number of non-native animals came to inhabit South American lands.

In the city of Trujillo, livestock was the greatest innovation introduced into Indigenous communities; they learned to raise pigs, goats, sheep, horses, mules, rams, and cattle (Quesada, 2013: 71).

For food consumption, the city of Trujillo was supplied with sheep, cattle, and bovines from the province of Huamachuco (Castañeda, 2009: 170; Quesada, 2013). The animals were driven from the highlands through the Virú Valley, taking advantage of the natural route to the province, and from there they were taken to Trujillo to be processed at the slaughterhouse or camalii, located outside the city for health reasons (Castañeda, 1996: 170–1).

Figure 1. Animals introduced during the colonial period in Trujillo. Drawings by Martínez de Compañón (1985).

Land use for grazing: herding in Trujillo and its valleys

Animal husbandry practices were of great importance in the Spanish colonies; the Crown encouraged animal breeding as an economic and social incentive for the relocation of Hispanic populations to the Americas (Barrio, 2019). After the conquest, the introduction of European domestic species increased at the hands of encomenderosiii (Salas, 2020), which displaced native herds from their natural habitat. With this appropriation of land for agriculture and ranching, estanciasiv were established, where reshaping the territory and delimiting pastures in the valleys was essential to increase livestock reproduction (Quesada, 2013: 71).

There are in Trujillo many encomenderos and neighbors very rich in rents, estates, and herds of large and small livestock, and above all famous sugar mills, which yield great income. It is certain that, if the port of this city, two leagues away and called Huanchaco, were safe and easy for embarkation and landing, Trujillo would be one of the most prosperous and opulent cities of the Realm (Murua, 1987: CHAPTER XVIII).

In the case of Trujillo, the encomenderos organized their own production enterprises around 1537 (Contreras and Hernández, 2017). By the seventeenth century, seasonal movements of herds from Andean estancias toward the city were recorded, forcing passage through the chaupiyunga of the Chao and Guañape valleys, the busiest access routes from the highlands to the coast, which were favored by extensive grasslands (Castañeda and Millaire, 2015).

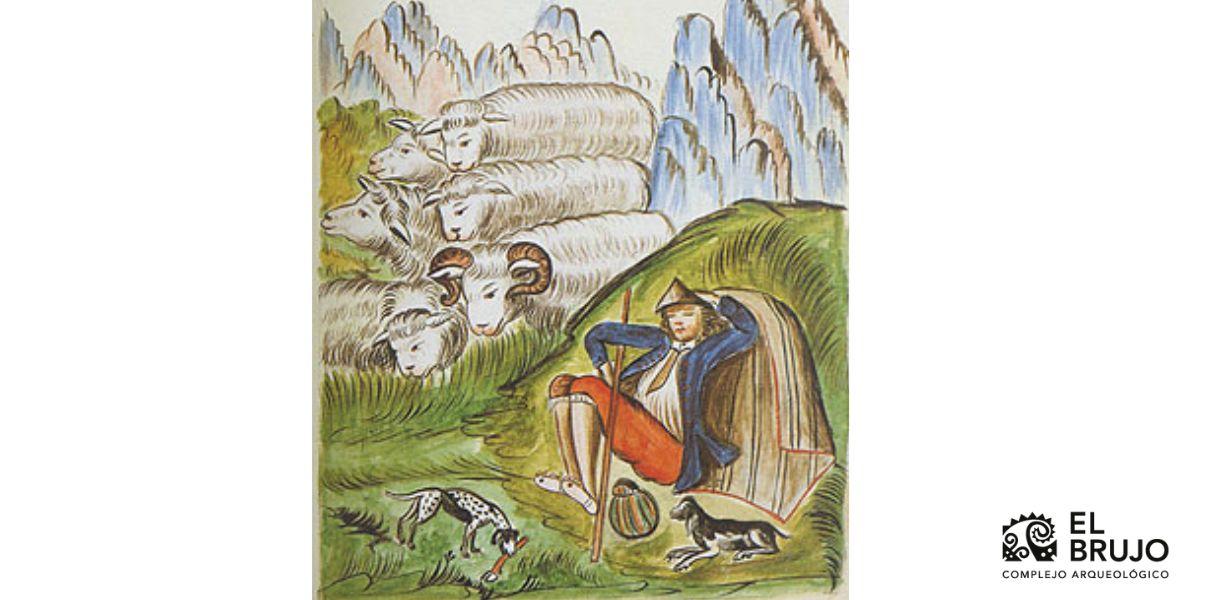

Figure 2. Indigenous person herding their sheep (Martínez de Compañón, 1985).

Livestock in Magdalena de Cao: dietary change and new inputs for production

During the reduction of Santa María Magdalena de Cao, located at the northern end of the Cao Viejo, the Indigenous town adopted a varied diet, shifting from agricultural and marine resources to one complemented by herding and livestock raising, specifically sheep and goats (Vásquez et al., 2020).

Although fully documenting the change in the subsistence economy of the former inhabitants of Magdalena and discussing native relocation during the reduction remains pending, it is clear that local populations had access to and consumed these resources.

Among the identified domestic animals, sheep, goats, and cattle appear most frequently compared to other species (Vásquez et al., 2020: 98–9). These results show that sheep and goats were slaughtered before reaching maturity, suggesting exploitation for meat and other by-products: milk and leather (Vásquez et al., 2020).

Figure 3. List of non-native animals identified based on bone remains from the colonial sector (Vásquez et al., 2020: 85).

And you—do you know of other animals brought with the Spanish conquest?

In ancient Peru, dogs, camelids, and guinea pigs were a fundamental part of daily life, and with the arrival of the Spanish the supply and consumption diversified. By visiting the archaeological complex El Brujo you can understand the importance of these species, their role in the diet, and their place in other economic activities.

Endnotes

i Garcilaso de la Vega (1970[1609]) records a variety of animals in Cuzco: cattle in 1550, sheep around 1556, and donkeys the following year (Vásquez et al., 2020: 103).

ii The rastro or camal are facilities dedicated to the slaughter of animals to continue the different processes for consumption (diet and raw materials).

iii The encomendero was a key figure within the tributary pact, especially in the early sixteenth century, when he became the first instance in the protection of Indigenous people and their interests. He was responsible for the care of his assigned Indigenous communities as well as their proper Christian doctrine (Cuevas and Castañeda, 2019: 165).

iv The estancia was a productive unit where agricultural and livestock activities were carried out and, at times, some manufacture such as weaving, tanning, carpentry, cheesemaking, etc. (Gonzáles and Grana, 2014: 168–9).

References

Barrio, M. (2019). The traces of livestock in the Matlatzinco Valley in the sixteenth century through Hispanic-Indigenous maps. Relaciones. Estudios de Historia y Sociedad, 40(160), 35–72.

Castañeda, J. (1996). Notes for a History of the City of Trujillo of Peru in the Seventeenth Century. In H. Tomoeda & L. Millones (Eds.), The Andean Tradition in Modern Times (pp. 159–189).

Castañeda, J., & Millaire, J.-F. (2015). Water, land, and resources. An environmental history of the Virú Valley, sixteenth–nineteenth centuries. PERSPECTIVAS LATINOAMERICANAS, 12, 50–67.

Contreras, C., & Hernández, E. (2017). Economic History of Northern Peru. Lordships, haciendas, and mines in the regional space. IEP.

Cuevas, H., & Castañeda, A. (2019). Indians and encomenderos: Approaches to the encomienda from political culture and the tributary pact. Cauca River Valley, 1680–1750. HiSTOReLo. Revista de Historia Regional y Local, 11(22), 165–197.

De la Vega, G. (1970[1609]). Royal Commentaries of the Incas and General History of Peru, Part One. Translated by Harold V. Livermore. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Gonzáles Navarro, C., & Grana, R. (2014). Stewards and regulation of Indigenous social practices in colonial estancias: The visit of Luxán de Vargas, Córdoba, 1692–1693. Revista Historia y Justicia, 3, Article 3.

Iniesta, M. L., Ots, M. J., & Manchado, M. (2020). Pre-Hispanic and early colonial food practices and traditions in Mendoza (central west Argentina). A contribution from archaeology and ethnohistory. Rivar (Santiago), 7(20), 46–66.

Lefebvre, K., & Manin, A. (2019). Preliminary reflections on the introduction of European herding practices in a rural Mesoamerican community in New Spain. ARCHAEOBIOS, 1(13), 41–65.

Martínez Compañón, B. J. (1985). Trujillo of Peru: Vol. II (Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional).

Salas, M. (2020). Manufactures and prices in colonial Peru, textile production and the domestic market, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In C. Contreras (Ed.), Compendium of the Economic History of Peru. Economy of the Early Colonial Period (pp. 447–531). BCRP, IEP.

Salazar-Soler, C. (2020). Mining and currency in the early colonial period. In C. Contreras (Ed.), Compendium of the Economic History of Peru. Economy of the Early Colonial Period (pp. 109–228). BCRP, IEP.

Quesada, A. (2013). On eating and drinking. Food culture in the city of Trujillo (1600–1720) [Undergraduate thesis]. Universidad Nacional de Trujillo.

Vásquez, V., Rosales, T., & Quilter, J. (2020). Plants and Animals. In J. Quilter (Ed.), Magdalena de Cao. An Early Colonial Town on the North Coast of Peru: Vol. Papers (pp. 77–106).

Researchers , outstanding news