- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Visitor Regulations

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

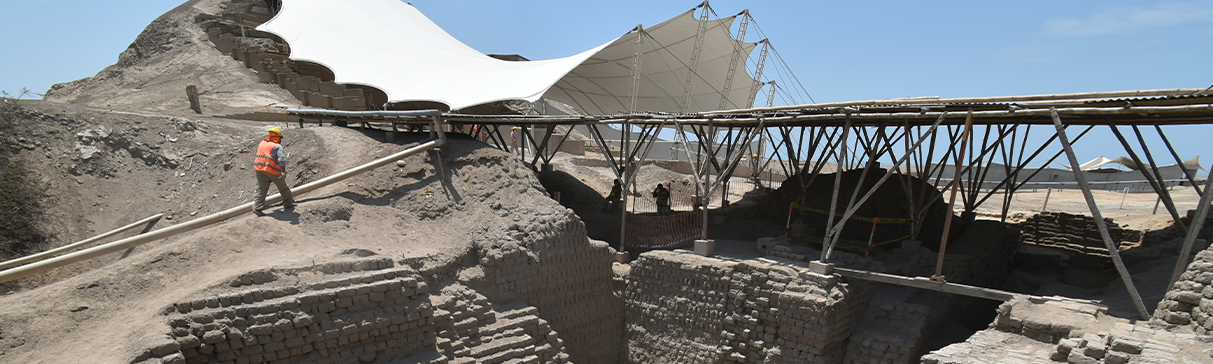

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- Pre-Hispanic Construction Materials: Adobe at El Brujo

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

PUCP Archaeology Students Visit the El Brujo Archaeological Complex ...

The Republican Settlements of El Brujo: Notes for the Recent History of Magdalena de Cao ...

To receive new news.

By: Yuriko Garcia Ortiz

Adobe was the most widely used pre-Hispanic building material for the construction of huacas along Peru’s northern coast. Together with secondary materials such as wood, stone, and cane, adobe bricks come in a wide variety of shapes that allow archaeologists to identify production methods, construction stages, and even social aspects of ancient life.

Pre-Hispanic Adobes on the North Coast

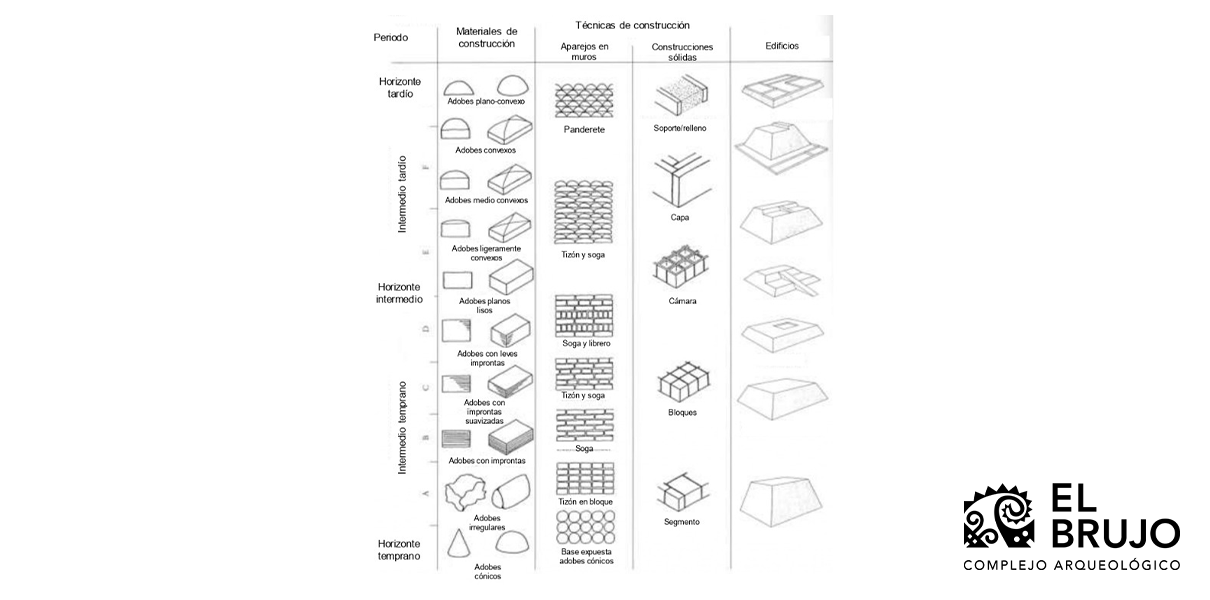

Building on the work of Ubbelohde Doering in northern Peru, Marcus Reindel (1993) established a relative chronology based on adobe typology, masonry techniques, monumental architecture, access routes, and iconography. His comparative study examined 123 archaeological sites from the Early Intermediate Period (200 BCE – 600 CE) to the Late Horizon (1476 – 1532 CE) across valleys such as Lambayeque, Zaña, Jequetepeque, Chicama, Moche, and Virú.

The long pre-Hispanic occupation of these sites offers valuable insights into the study and classification of ancient building materials. For instance, during the Formative Period (1700 – 200 BCE), conical adobes were common in monumental architecture, while in later periods rectangular or parallelepiped adobes became standardized, often mass-produced with cane molds, eventually evolving into plano-convex adobes (Reindel, 1993: 134).

Figure 1. Relative chronology of architectural typology (Reindel, 1993: Tab. 5)

Moche Adobes at El Brujo

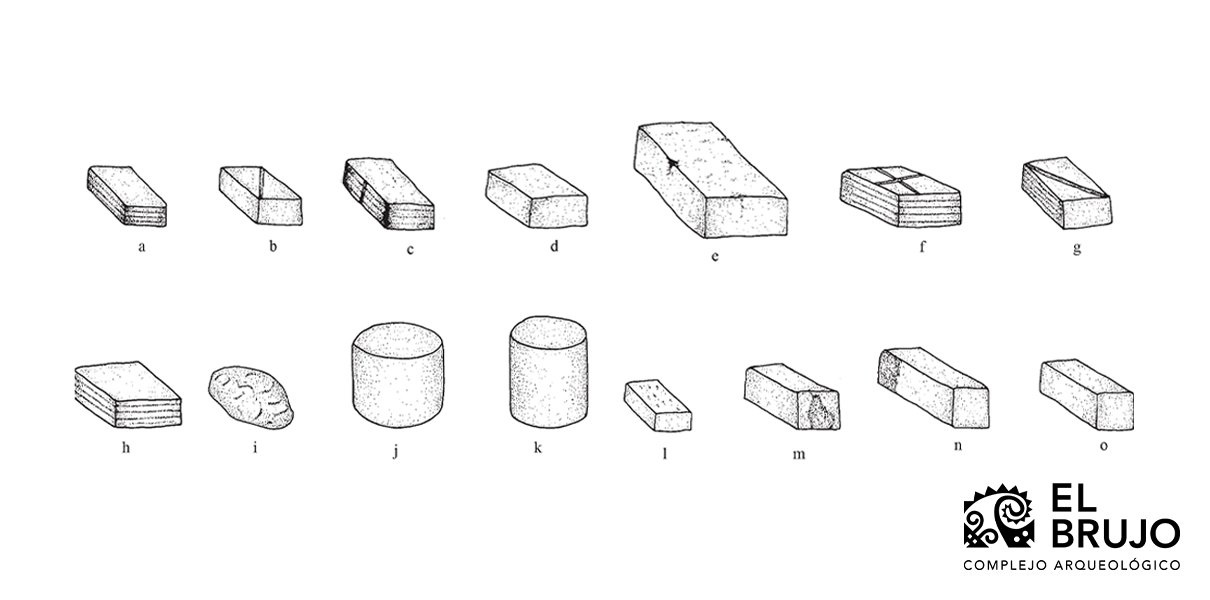

At Huaca Cao Viejo, the basic construction materials include rectangular adobes (a–h), plano-convex adobes (i), square adobes (m–o), and cylindrical adobes (j–k) (Gálvez et al., 2003: 80). Analysis of these materials provides key evidence for understanding the diversity of forms used in both initial construction and later architectural renovations.

Recent excavations in the Eastern Annex and Western enclosures revealed large-scale use of parallelepiped adobes in walls and adobe-block lattice fillings (bloques de adobe tramado or BAT), as well as cylindrical adobes sealing off certain ceremonial spaces (Bazán & Alva, 2024; Acero & Avila, 2024: 232–5).

Some adobes are displayed in Room 3 of the El Brujo Site Museum, but visiting the complex itself—via the classic or specialized route—offers a unique chance to appreciate its monumentality, construction techniques, ceremonial functions, adaptation to the environment, and use of local resources.

Figure 2. Typology of adobes used in the construction of Huaca Cao Viejo (Galvez et al. 2003, 81).

Marked Adobes During the Early Intermediate Period (200 – 600 CE)

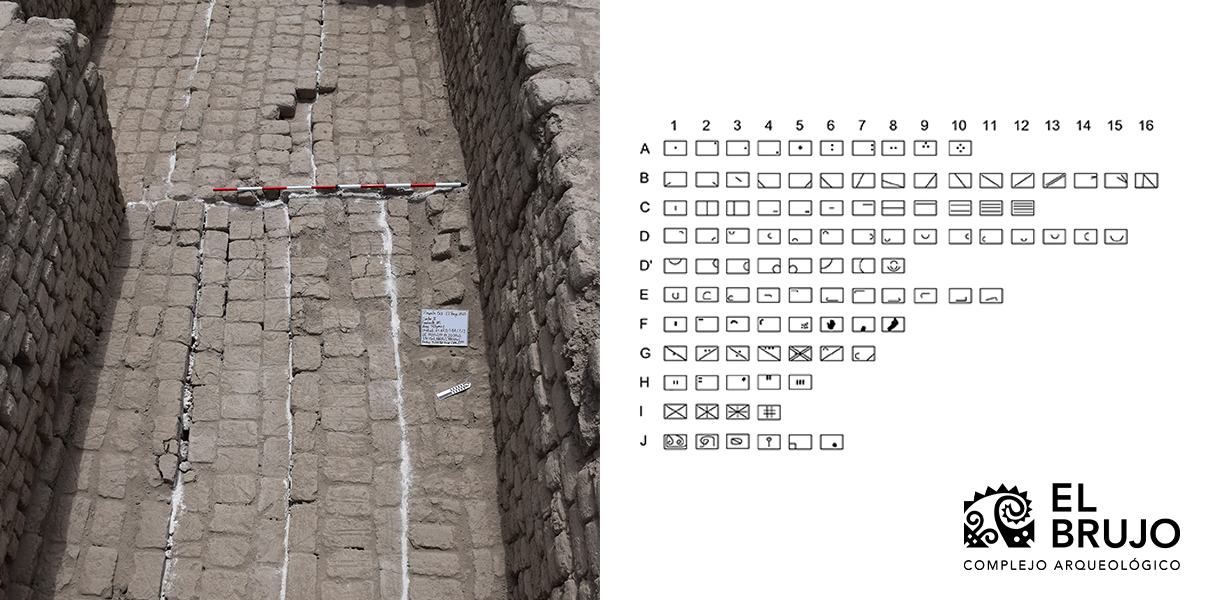

A hallmark of Moche architecture is the use of marked adobes—bricks stamped or imprinted while the clay was still wet, often referred to as “makers’ marks” (Reindel, 1993: 427). These symbols vary widely, with many recurring across major sites such as Huaca Rajada (Alva & Donnan, 1993), Huaca Bola de Oro-El Triunfo (Bracamonte, 2015), Huaca El Pueblo (Bourget, 2016), Huaca Dos Cabezas (Donnan, 2007), Huaca Cao Viejo (Franco et al., 1993), and Huacas del Sol y de la Luna (Hastings & Moseley, 1975).

Figure 3. Dog footprint next to the scale, and a human footprint on the right.

The manufacture and use of adobes shed light on the organization of labor in Moche society (Tsai, 2012). At Huaca Cao Viejo, two groups of marks were identified:

- Animal and human prints – dog paw marks suggest close interaction with domestic animals, while fingerprints, handprints, and footprints of adults and children reflect communal participation in adobe production.

- Geometric and linear symbols – analyzed to classify brick groupings within construction fills, representing possible social groups or work teams (Moseley, 1975: 192).

Approximately 208 different symbols have been recorded at Huaca Cao Viejo (Franco et al., 1993, 1994; Gálvez et al., 2003). In the Eastern Annex alone, 102 symbols were identified across 9,225 adobes (Zapata et al., 2024), some resembling those documented at Huaca del Sol and Huaca de la Luna (Hastings & Moseley, 1975: 199).

Figure 4. Marked adobes in the East Annex of Huaca Cao Viejo (Zapata et al., 2024: 102–05).

Were Marked Adobes Exclusively Moche?

During the Middle Horizon (600 – 900 CE), new urban and ceremonial centers emerged in the Chicama Valley. Post-Moche societies also produced marked adobes, using different symbols, adobe forms, and architectural styles that reflected their own cultural identity.

Want to Know How Adobes Were Made?

Even today, adobe makers preserve traditional techniques. To produce bricks of different sizes, artisans follow time-tested recipes. Julio López, an adobe craftsman from the Casma Valley, shares his expertise in keeping this ancestral practice alive.

References

Acero, E., & Avila, M. (2024). Las excavaciones en la plataforma superior. En A. Bazán & J. Alva (Eds.), Reevaluando la cronología de la Huaca Cao Viejo, Complejo Arqueológico El Brujo. Reporte integral de investigaciones de campo de la temporada 2020 (pp. 190-247).

Alva, W., & Donnan, C. B. (1993). Tumbas Reales de Sipán. Fowler Museum of Culture History.

Bazán, A., & Alva, J. (2024). La coyuntura cronológica. La ocupación Mochica en el complejo El Brujo y la secuencia constructiva de la Huaca Cao Viejo. En A. Bazán & J. Alva (Eds.), Reevaluando la cronología de la Huaca Cao Viejo, Complejo Arqueológico El Brujo. Reporte integral de investigaciones de campo de la temporada 2020 (pp. 22-73).

Bourget, S. (2014). Les rois mochica: Divinité et pouvoir dans le Pérou ancien (Illustrated édition). EVERGREEN.

Bracamonte, E. (2015). Huaca Santa Rosa de Pucalá y la organización territorial del valle de Lambayeque (Unidad Ejecutora 005 Naylamp Lambayeque).

Donnan, C. (2007). Moche Tombs at Dos Cabezas. The Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press.

Franco, R., Gálvez, C. & Vásquez, S. (1994). Proyecto Arqueológico Complejo «El Brujo». Programa 1994 (Informe Final). Lima: Fundación Wiese, Instituto Nacional de Cultura - La Libertad, Universidad Nacional de Trujillo.

Franco, R., Gálvez, C. & Vásquez, S. (1993). Proyecto Arqueológico Complejo «El Brujo». Programa 1993 (Informe Final). Lima: Fundación Wiese, Instituto Nacional de Cultura - La Libertad, Universidad Nacional de Trujillo.

Gálvez, C., Murga, A., Vargas, D., & Ríos, H. (2003). SECUENCIA Y CAMBIOS EN LOS MATERIALES Y TÉCNICAS CONSTRUCTIVAS DE LA HUACA CAO VIEJO, COMPLEJO EL BRUJO, VALLE DE CHICAMA. En S. Uceda & E. Mujica (Eds.), Segundo Coloquio sobre la Cultura Moche (pp. 79-118).

Hastings, C. M., & Moseley, M. E. (1975). The Adobes of Huaca del Sol and Huaca de La Luna. American Antiquity, 40(2Part1), 196-203.

Moseley, M. Edward. (1975). Prehistoric Principles of Labor Organization in the Moche Valley, Peru. American Antiquity 40 (2): 191-196.

Reindel, M. (1993). Monumentale Lehmarchitektur am der Nordküste Perus. Eline Representative Untersuchung nach-formativer Grobbauten von Lambayeque-Gebiet bis zum Viru-tal. Bonner Amerikanistische Studien 22. Bonn.

Tsai, H. I. (2012). Adobes y la organización del trabajo en la costa norte del Perú. Andean Past, 10, 133-169.

Zapata, C., Pérez, E., & Albornoz, K. (2024). Las excavaciones en el anexo este. En A. Bazán & J. Alva (Eds.), Reevaluando la cronología de la Huaca Cao Viejo, Complejo Arqueológico El Brujo. Reporte integral de investigaciones de campo de la temporada 2020 (pp. 94-189).

Researchers , outstanding news