- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Visitor Regulations

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- Series on Andean Food: The Llama and the Alpaca

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

PUCP Archaeology Students Visit the El Brujo Archaeological Complex ...

The Republican Settlements of El Brujo: Notes for the Recent History of Magdalena de Cao ...

To receive new news.

By: José Ismael Alva Ch. y Leslie Zúñiga Becerra

By José Ismael Alva Ch. and Leslie Zúñiga Becerra

The llama and the alpaca are South American camelids domesticated from the ancient species of guanacos and vicuñas (wild camelids), respectively. Commonly used as pack animals and utilized in the production of fabrics, the meat from these camelids was, and continues to be, one of the most abundant sources of animal protein, when compared to chicken and beef. Join us on this occasion to review the history of these popular camelids and their differences, as well as the ways to consume them and their nutritional properties.

Llama and Alpaca: In what geographical areas do they live?

Currently, the llama and the alpaca are distributed mainly in the highlands of Peru and Bolivia, though they can also be found, to a lesser extent, in the high Andean ecosystems of Argentina and Chile. However, archaeological and historical information shows that during pre-Hispanic times the distribution of these animals was greater and encompassed most of the ecological levels defined by the Andes Mountains, given that camelids are the best adapted to the various geographic conditions of South America [1] [2].

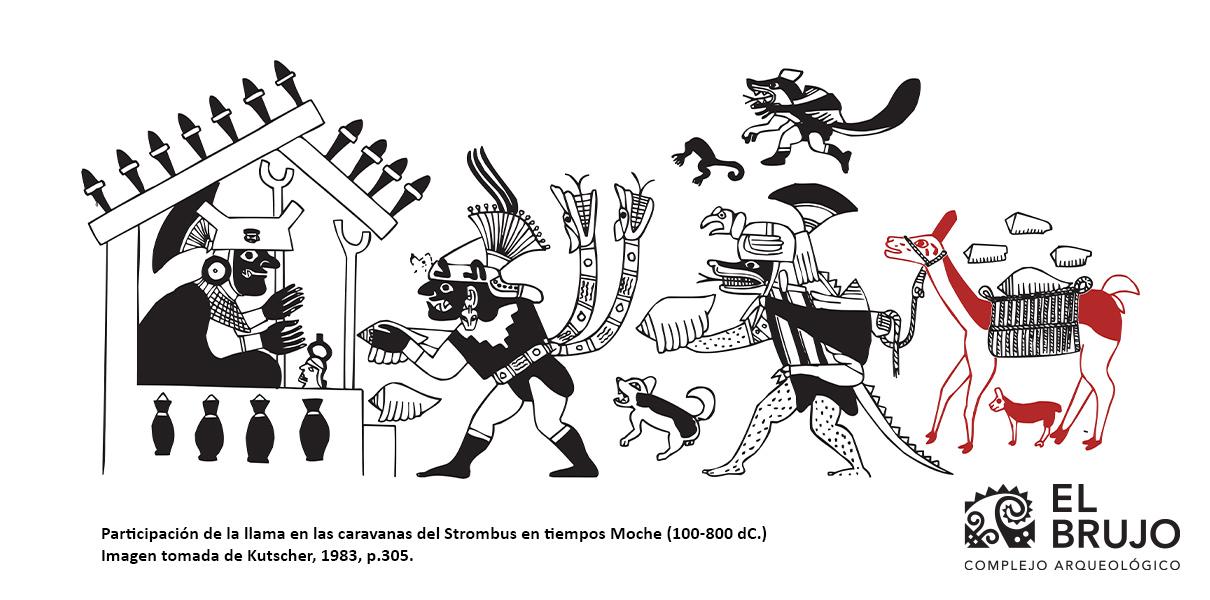

Recent laboratory studies carried out on the bones of the Mochica camelids (100-800 AD) from the El Brujo Archaeological Complex and the Huaca de La Luna show that the rearing of llamas and alpacas occurred in a sustained manner in the lower and intermediate valleys of the coast [3].

The domestication of camelids

According to the archaeological research carried out in the highlands of Junín, in the Central Andes of Peru, the domestication of the llama and the alpaca was a long process that began 6 000 years ago and spanned around 2 millennia. This process implied a knowledge of the biological cycles of the guanaco and the vicuña in their wild state by the Andean inhabitants, and marks the transition from the hunting economy to shepherding [1] [2].

Aside from food consumption, which we will see further along, the differences in the domestication of the llama and the alpaca was the use of their characteristics. Thus, the llama was progressively prioritized as a pack animal, while the alpaca was raised mainly to use its fibers in textile production.

Representation of a pack of llamas in a XVII century engraving. Taken from the work "America ..." by the Scottish cartographer John Ogilvy (1671).

Main biological characteristics

The Llama

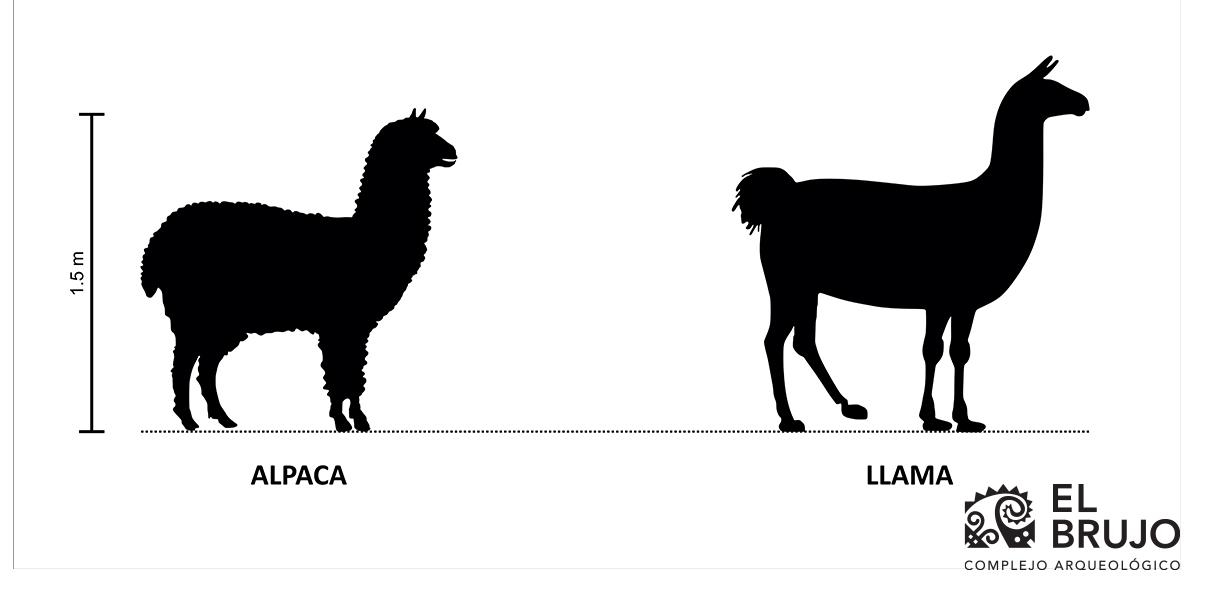

The llama is the largest species of South American camelids. It reaches a height of 1.20 m at the withers. Its average weight is 110 kg, although it can reach 150 kg. Due to their physiological adaptation, these camelids have a greater preference to eat dry and fibrous forages, commonly avoided by other animals. The llama's gestation period is approximately 10.5 months and births take place between the months of January and March, a time when there is the greatest amount of pasture for the young. The wool that covers its body is short and rough, compared to that of the alpaca, but its fiber can be used for clothing [1].

The Alpaca

Alpacas produce more and better quality wool than llamas. They reach 1 m at the withers. The weight of this animal is around 64 kg. Unlike llamas, alpacas select the grasses they consume according to their seasonal availability, having a preference for fresh forages. Although these camelids can live off the consumption of dry grasses, this causes the wool and meat to be of poor quality. Regarding the gestation period, the alpaca spans 11 months and births occur during the rainy season in the highlands [1].

Camelids and diet in the pre-Hispanic Andes

Since their domestication, the llama and the alpaca have been skillfully exploited as a resource throughout pre-Hispanic history. Apart from taking advantage of their carrying and transport capacity, hair, hide and bones, among others, were used to produce clothing, footwear, and tools for socio-economic maintenance and in religious contexts. However, on this occasion we are interested in reviewing the forms of food consumption [1] [2] [4].

In ancient Peru, the consumption of camelid meat was one of the main sources of protein in the diet and allowed a balanced nutrition. In particular, the dehydrated meat of these animals, or ch'arki, was the common processing for its storage and guaranteeing its availability at different times of the year [5].

It is not known with certainty since when Andean populations began to produce and consume ch'arki. However, archaeological research has made it possible to state that dried camelid meat had a high consumption in the most exclusive sectors of the ceremonial center of Chavín de Huántar (1200 - 500 BC), while the residences of its artisans maintained the consumption of fresh meat [6] [7].

According to chroniclers such as José de Acosta and Bernabé Cobo, the meat of the llama and the alpaca had a taste that was pleasant and similar to that of the cow. In the XVI and XVII centuries, ch'arki was the common way of eating the meat of domesticated camelids. Although written sources do not detail the ways of making ch'arki, it is indicated that the meat of adult animals was used in order to salt and dry it in the sun [4] [5].

"The meat of these [animals] is good, though tough: that of their lambs* is one of the best things, and most gifted** that one can eat ..." - José de Acosta, 1590

Is camelid meat consumed nowadays?

Yes, although its consumption is not very widespread. It can be purchased fresh or dehydrated. The fresh meat is used to prepare typical soups accompanied with potatoes, called chupes, and locros (squash stews). It is also consumed in traditional dishes such as Pachamanca (pit roast) accompanied with other Andean products. The dehydrated form is still called Ch'arki or Chalona, which in Quechua means “dried, smoked meat”. The meat is cut into thin slices, covered with plenty of coarse salt and exposed to the sun for 15 or 20 days. Currently, there are several novel restaurants, both in Peru and in the world, that prepare gourmet dishes based on alpaca meat [8].

The quality and flavor of the meat depends on the age of slaughter. If they are very young, the meat will have a poor conformation and low weight. The best ages are between 36 and 44 months. In males, the flavor is stronger [8].

Unfortunately, in Peru there are no specialized centers for the sale of llama and alpaca meat (with the exception of the sales center of Universidad Agraria de la Molina), unlike our border neighbors Chile and Bolivia [9].

The benefits of consuming Llama and alpaca meat

Llama and alpaca meat is high content in protein, iron and is low in fat and cholesterol. Compared to other meats, that of these camelids has a higher protein content (23.9%), compared to chicken (21.4%) and beef (21%) [2]. Furthermore, in 100 grams of llama and alpaca meat there is between 30 to 40 mg of cholesterol, while in chicken it is 88 mg and in beef 90 mg [10].

It is a great alternative for people who have excessively high levels of cholesterol or fats (lipids) in the blood, or who suffer from anemia, obesity and overweight. The minimum levels of cholesterol in alpaca meat make it recommendable for patients with cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and arterial hypertension [10].

As a curious fact in traditional medicine, the fat from the chest of the llama (unto or tustuca) is used for rubbing the chest of a patient with respiratory infections. It is also used for healing indigestion in children and for relieving bone pain, while consuming the placenta helps with infertility problems [8].

Nutritional value

* The Spanish commonly referred to the llamas as "Land Lambs" [4]. Consequently, the young camelids were renamed "lambs."

** According to the Treasure of the Castilian Language by Sebastián Covarruvias Orozco (1674, fol. 157), the word “gift” meant to treat food “with curiosity and gusto”.

Bibliography

[1] Bonavia, D. (1996). South American Camelids. An introduction to their study. Lima: Institut français d’études andines.

[2] Renieri, C., E. N. Frank, A. Y. Rosati and M. Antonini. (2009). Definition of breeds in llamas and alpacas. Animal Genetic Resources Information, 45, pp. 45-54.

[3] Dufour, E., N. Goepfert, B. Gutiérrez, C. Chauchat, R. Franco, S. Vásquez. (2014). Pastoralism in Northern Peru during Pre-Hispanic Times: Insight from the Moche Period (100-800 AD) Based on Stable Isotopic Analysis of Domestic Camelids. Plos One, 9 (1), pp. 1-20.

[4] Cobo, B. (1964 [1653]). History of the New World. First part. Library of Spanish Authors Volume XCI. Madrid: Atlas editions.

[5] Antunez de Mayolo, S. (1981). Nutrition in Ancient Peru. Lima: Central Reserve Bank of Peru

[6] Miller, G. and R. Burger. (1995). Our father the Cayman, our dinner the llama: Animal utilization at Chavin de Huantar, Peru. American Antiquity, 60 (3), pp. 421-458.

[7] Rosenfeld, S. and M. Sayre. (2016). Llamas on the land: Production and consumption of meat at Chavín de Huántar, Peru. Latin American Antiquity, 27 (4), pp. 497-511.

[8] DF, A. E., Montero, M., & Barros-Rodríguez, M. (2018). South American camelids: products and by-products used in the Andean region. Actas Iberoamericanas en Conservación Animal AICA, 11, 30-38.

[9] Ardiles, T. (January 13, 2020). Llama meat: rich in protein and low in cholesterol. Agronoticias, journal for development. https://agronoticias.pe/alimentacion-y-salud/articulos/carne-de-llama-rica-en-proteinas-y-baja-en-colesterol/

[10] Nacionalpe (March 19, 2016). They recommend consuming llama and alpaca meats against obesity and high blood pressure. [Press release]. https://www.radionacional.com.pe/informa/locales/recommend-consumir-carnes-de-llama-y-alpaca-contra-la-obesidad-e-hipertensi-n-arterial

[11] Reyes García, M., Gómez-Sánchez Prieto, I., & Espinoza Barrientos, C. (2017). Peruvian food composition tables.

Researchers , outstanding news