- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Visitor Regulations

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- The Andean Littoral Islands: Notes on their Economy and Rites in Pre-Hispanic Periods – part 1

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

PUCP Archaeology Students Visit the El Brujo Archaeological Complex ...

The Republican Settlements of El Brujo: Notes for the Recent History of Magdalena de Cao ...

To receive new news.

By: José Ismael Alva Ch.

By: José Ismael Alva Ch.

"and when they arrived on the Island, they worshiped the Huaca Huamancantac and the Lord of Huano, and they gave him the offerings, so that he would allow them to take the huano".

José de Arriaga, 1621, Cap. V, fol. 31

When the Spanish arrived in the Andes, they found a series of social groups with deep-rooted religious traditions, which were fought through the extirpation of idolatries in order to impose the Catholic dogma. The doctrinal priests, those who carried out evangelization work among the native communities, produced reports as a result of these campaigns. These documents depict a system of cults associated with existing shrines in edifices and, especially, in natural elements with a sacred character.

The sacralization of said natural elements went hand in hand with the elaboration of myths that explained the existence of natural phenomena and thus sustained and justified the social order. The myths and the cults had different nuances and emphases according to the region; as, for example, in the highlands there were various deities with attributes associated with thunder and rain, a situation that did not occur on the coast (Rostworowski, 1983, p. 94), where the myths highlighted the origin of the region's natural resources, especially those considered important for the support of social life.

In this panorama, the islands of the Andean coast were economically utilized and were incorporated into the belief system, through myths and the reiteration of rituals. This research note consists of two parts. In this first part, we will review the economic aspect of the islands, emphasizing two main activities: The hunting of sea lions and the collection of guano.

The islands and their resources

The islands of the Peruvian sea constitute ecosystems to which the ancient populations of the coast accessed after the development of navigation. Among the animal species that inhabit the islands, the sea lion is one of those that appear with the greatest written and archaeological reference.

The hunt for the sea lion

In "History of the New World", Father Bernabé Cobo gathered that, in the language of the Inca, sea lions were known as azuca. The hunting technique of these animals was done by means of accurate blows with a stick on their nose (Cobo 1964 [1656], p. 295). Some representations of this form of hunting appear in Moche pottery, where the characters brandish maces and attack a group of wolves on an island.

In the XVI century, chroniclers Gutiérrez de Santa Clara and López de Gómara pointed out that the natives of the coast used to cook sea lion meat and found it tasty (Rostworowski, 1981, p. 113). However, it seems that the nutritional consumption of the sea lion decreased in colonial times as, decades later, Bernabé Cobo (1964 [1656], p. 295) pointed out that “the meat of these lions is not eaten except in cases of necessity”.

Because of their high level of body fat, sea lions were hung with their skin flayed under the sun in order to collect oil. Depending on the size, nine to ten jars of oil could be obtained from each lion. This oil was used to light up the fields and to prevent corrosion on metal instruments (Ibid.).

Moreover, during the XVII century, on the coasts of Arica and Atacama, it was common to use the hide of sea lions to make rafts. These rafts were assembled as bags filled with air with which they entered the sea in order to fish (Ibid.).

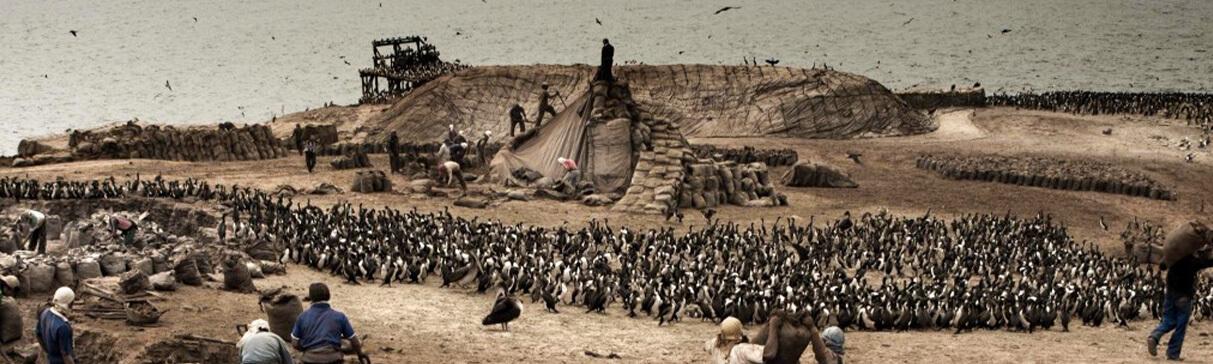

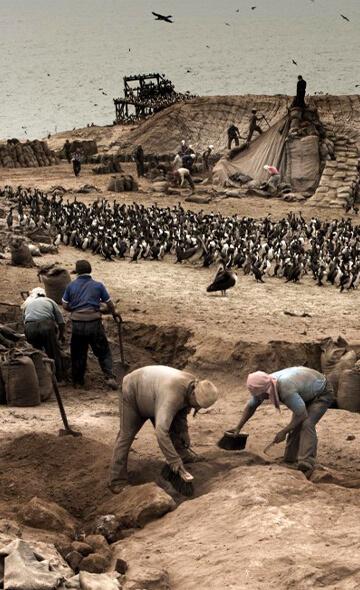

Guano harvesting

The guano of the islands, generated by the deposition of seabirds, is one of the best known and most appreciated agricultural fertilizers on the coast and in the mountains for the cultivation of corn since pre-Hispanic times (Buse, 1975, Volume II, Vol. 2, p. 619; Curatola, 1997, p. 230-231).

In eminently agricultural societies like the Andean ones, the supply of this kind of fertilizers was key to sustaining subsistence and the economy of human groups. Hence, during the Inca Empire, the imperial state issued the order to maintain surveillance and control over the birth rates of seabirds in order to guarantee the renewal of this resource (Garcilaso de la Vega cited in Curatola, 1997, p .231-232).

How much guano was used in the crops? At the beginning of the XIX century, the British explorer William Bennet Stevenson (1971 [1829], p. 198), attested that the corn fields in Chancay were fertilized with one ounce (28.3 grams) of guano for every three or four plants.

So far we have recounted the most outstanding economic activities in the archaeological and written records on the utilization of the islands. However, we cannot fail to mention other activities such as hunting seabirds to use the down (fine feather) in the manufacture of thermal clothing, as well as the collection of eggs; which must have been recurrent in the Andean past.

Taking into account this economic base and its importance in the sustenance of societies, we can understand the incorporation of the islands into the pre-Hispanic belief system and the ritual practices associated with them. The religious aspect of the islands and the case of the Macabí Islands, located on the coast of the Chicama Valley will be presented at the conclusion of this research note.

Bibliography

• Arriaga, J. (1621). Extirpation of the Idolatry of Pirú directed to King Nuestro Señor and his Royal Council of the Indies. Lima: Geronymo de Contreras, Book Printer.

• Bennet Stevenson, W. (1971 [1829]). Memoirs on the San Martín and Cochrane campaigns in Peru. In: List of Travelers. Documentary Collection of the Independence of Peru, E. Núñez (Comp.), Vol. III, 73-338.

• Buse, H. (1975). Maritime History of Peru. Prehistoric Epoch. Volume II, Volume 1 and 2. Lima: Institute of Historical-Maritime Studies of Peru

• Cobo, B. (1964 [1656]). History of the New World. First part. In: Library of Spanish Authors. Volume XCI. Madrid: Atlas editions.

• Curatola, M. (1997). Guano: a hypothesis about the origin of the wealth of the Chincha nobility. In: Archeology, Anthropology and History in the Andes. Tribute to María Rostworowski, R. Varón and J. Flores (Eds.), Pp. 223-239. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Andinos, Banco Central de Reserva del Perú.

• Hocquenghem, A. M. (1987). Mochica iconography. Lima: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

• Rostworowski, M. (1981). Renewable Natural Resources and Fishing. XVI and XVII centuries. Lima: Institute of Peruvian Studies.

• Rostworowski, M. (1983). Andean Power Structures. Lima: Institute of Peruvian Studies.

Researchers , outstanding news