- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Visitor Regulations

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- The Mochica: Lords of the North Coast of Pre-Hispanic Peru

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

PUCP Archaeology Students Visit the El Brujo Archaeological Complex ...

The Republican Settlements of El Brujo: Notes for the Recent History of Magdalena de Cao ...

To receive new news.

By: José Ismael Alva Ch.

José Ismael Alva Ch.

When we speak of the Mochica, or Moche, we refer to the beginnings of Peruvian archeology. Max Uhle, Alfred L. Kroeber and Rafael Larco Hoyle are the names of the pioneering researchers who made known, during the first half of the 20th century, the existence of an ancient cultural expression on the North Coast of pre-Columbian Peru, which was characterized by the production of fine ceramics that commonly represented scenes related to religion and the exercise of power.

Based on the archaeological research conducted in recent decades, we present what we know about the Mochica today. Although there is no full consensus among specialists, this note seeks to make a brief synthesis on the basic aspects of the Mochica phenomenon. The more thorough readers and those in search of more information can review the sources of this text in the bibliography section.

The origins of the Mochica

The Peruvian researcher Rafael Larco Hoyle originally proposed that the Mochica constituted a centralized state with a capital city. However, this thesis is untenable today. There is much evidence that indicates the existence of several Mochica entities sharing similar cultural codes between 100 and 800 AD. (Castillo and Donnan, 1994). The thesis most sustained is that the origin of the Mochica occurred within the Gallinazo society (200 BC to 100 AD), which developed some 300 years earlier (Millaire et al, 2016).

By the year 100 AD an elite emerged that inherited ancient ceremonial traditions from the Formative period and designed a religious system that was adopted by various power groups settled in the valleys of the north coast, generating a rupture within the Gallinazo society (Bawden, 1994, p. 398; Quilter, 2010, p. 235). This elite expanded and consolidated the religious system, using the construction of temples and acquiring a fundamental role in the government of society.

Mochica objects and power

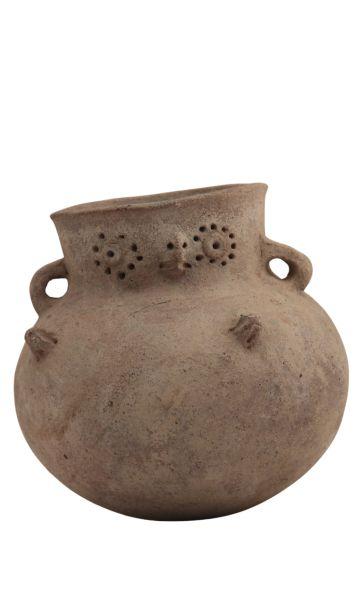

Also, the Mochica elites promoted the production of a repertoire of fine objects (ceramics, metal, mural art and wooden sculptures, among other materials), under a general style conducted by outstanding artisans. These objects were of the utmost importance, given their role as media for capturing cultural codes (iconography) and communicating the belief system based on the existence of fearsome supernatural beings, the exacerbation of social hierarchies, the confrontation among warriors and the sacrifice of those subdued.

The Mochica Elites

Behind the temples, objects and religion, there was a social group that was concentrating greater political power, placing itself at the top of the old Gallinazo social structure (Bawden, 1994; Castillo and Uceda, 2008). We identify this elite and its religious system as Mochica, or Moche. Examples of this social segment are: The Lord of Sipán and the old Lord of Sipán (Lambayeque), The Lord of Úcupe (Zaña valley), The Lady of Cao (Chicama valley), as well as other high-ranking personages who wore emblems of power widely represented in the iconography of the time.

The Mochica Territory

In the late 1980s, archaeologists discussed the existence of a single and powerful Mochica State with its capital in the settlement comprised of the Huaca de La Luna and the Huaca del Sol (Moche Valley), a proposal initially raised by Larco Hoyle, and which enjoyed great popularity among academics and the community in general for more than four decades (Bawden, 1994; Castillo and Donnan, 1994; Castillo and Uceda, 2008).

With the intensification of archaeological studies, we now know not only that the distribution of the Mochica is ample, as they covered fourteen valleys of the North Coast, from Piura to Huarmey (Giersz, 2011), but also that the occupation of this territory was not homogeneous or continuous. This was due, apart from geographical factors, to the social and cultural particularities of the pre-existing populations and to the political strategies undertaken by the Moche elites with their own interpretation of the dominant religious discourse.

Thus, based on the marked variations of the Mochica ceramic style and the differences in their historical paths, archaeologists have proposed the existence of two large Mochica territories: a northern one, from Alto Piura to the Jequetepeque valley; and another, southern one, made up of a series of valleys from Chicama to Huarmey. Within these territories, each valley would have developed political entities divided into social classes.

The end of the Mochica

Between the years 600 and 650 AD, the Mochica settlements underwent a series of important changes after a climate crisis (the El Niño phenomenon) and due to the tension generated by the Wari expansion (Koons, 2014, p. 1051). The "endings" or "collapses" occurred in different intensities and times, apparently marked by the political decisions made by the Mochica elites of the South and North.

In the southern territory, whose main area was the Chicama and Moche valleys, the Moche elites had promoted the production of huaco-portraits, sculptural vessels that represented the Moche leaders, in an effort to shift the ideological focus to their figure and accumulate more power within society (Bawden, 1994). The high frequency of this type of vessel in the South demonstrates the emphasis and relative success of this strategy. However, with the deep regional crisis, social tensions turned towards the image of the leaders, causing the discrediting of the Moche belief system and the abandonment of their temples (Bawden, 1994, p. 402, 407).

On the other hand, the northern territory shows that the adjustments to the Moche religious discourse allowed the survival of its elite, but it was destined for a slow agony. The ostentatious tomb of the Lord of Sipán (610 - 715 AD) corresponding to this time, reveals that some northern Mochica rulers preserved their power in times of social crisis (Aimi et al, 2016). Furthermore, extensive settlements with high population density achieved greater prominence. Such is the case of Pampa Grande (Lambayeque), where, unlike the South Moche, the temple maintained a prominent position until its abandonment in 750 AD. (Bawden, 1994).

A region of stories

The North Coast of Peru is heir to an ancient history of pre-Columbian peoples. In this process, the Mochica stood out for the emphasis they devoted to the production of fine objects with high symbolic value and to the construction of ceremonial centers filled with religious figures. Our knowledge about the rise and fall of the Mochica has been renewed in recent decades, and will continue to do so in the following years with further archaeological research.

Finally, after the decline of the Mochica in both territories, new power groups assumed control of societies with even more distinct cultural traits among them. We know them as: The Lambayeque in the North, and the Chimú in the South.

Bibliography

• Aimi, A., Alva, W., Chero, L., Martini, M., Maspero, F., & Sibila, E. (2016). Towards a new chronology of Sipán. In A. Aimi, K. Makowski, & E. Perassi (Eds.), Lambayeque. New Horizons of Peruvian Archeology (pp. 129–156). Ledizioni.

• Bawden, G. (1994). The structural paradox: Moche culture as a political ideology. S. Uceda and E. Mujica (Eds.), Moche: Proposals and Perspectives (pp. 389-412). Trujillo: National University of La Libertad.

• Castillo, L. and Donnan, C. (1994). The Mochica of the North and the Mochica of the South. Vicús, pp. 143-181. Lima: Banco de Crédito del Perú.

• Castillo, L. and Uceda, S. (2008). The Mochicas. H. Silverman and W. Isbell (Eds.), Handbook of South American Archeology (pp. 707-729). New York: Springer.

• Giersz, M. (2011). The guardians of the southern border: the Moche presence in Culebras and Huarmey. M. Giersz and I. Ghezzi (Eds.), Archeology of the Ancash Coast (p. 271-309). Lima/Warsaw: Institut français d’études andines, Center for Pre-Columbian Studies of the University of Warsaw.

• Koons, M. L. (2014). Revised Moche chronology based on Bayesian models of reliable radiocarbon dates. Radiocarbon, 56 (3), 1039-1055.

• Millaire, J-F., Prieto, G., Surette, F., Redmond, E. M. and Spencer, C. S. (2016). Statecraft and expansionary dynamics: A Virú outpost at Huaca Prieta, Chicama Valley, Peru. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113 (41). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1609972113

• Quilter, J. (2010). Moche: Archeology, Ethnicity, Identity. Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Études Andines, 39 (2), 225-241.

• Quilter, J. and Koons, M. (2012). The fall of the Moche: A critique of claims for America’s first state. Latin American Antiquity, 23 (2), 127-143.

• Uceda, S. E., Gayoso, H. L. and Gamarra, N. V. (2016). The Gallinazo in Moche, Style or Culture? A problem to be solved: The Case of the Huacas de Moche. S. Uceda, R. Morales and C. Rengifo (Eds.), Rsearch in the Huaca de La Luna 2005 (pp. 321-334). Trujillo: Board of Trustees of Huacas del Valle de Moche – Universidad Nacional de Trujillo.

Researchers , outstanding news