- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Visitor Regulations

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- Ornaments of Power of the Lady of Cao: Maces

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

PUCP Archaeology Students Visit the El Brujo Archaeological Complex ...

The Republican Settlements of El Brujo: Notes for the Recent History of Magdalena de Cao ...

To receive new news.

By: Yuriko Garcia Ortiz

Maces form part of the group of offensive weapons (Pérez, 1999: 325–26) most frequently represented in Moche war scenes (Donnan, 2004; Golte, 2016). According to the iconographic repertoire, museum collection studies, and archaeological findings along the north coast, different types of maces have been identified: conical, circular and star-shaped with six or more points. Their manufacture also involved diverse raw materials, including botanical (wood), metal and ceramic (Pérez, 1999: 329–30; Chamussy, 2014).

Accompanying elite figures, maces were symbols of power (Franco, 2021). They were present in ritual ceremonies (Franco et al., 1999) and, in offensive contexts, are commonly associated with battles (Donnan, 1978) and hunting scenes (Kutscher, 1983).

The maces of the Lady of Cao’s funerary bundle

The funerary context of the Lady of Cao, associated with the second building of Huaca Cao Viejo, is one of the most important ever recorded at the El Brujo Archaeological Complex.

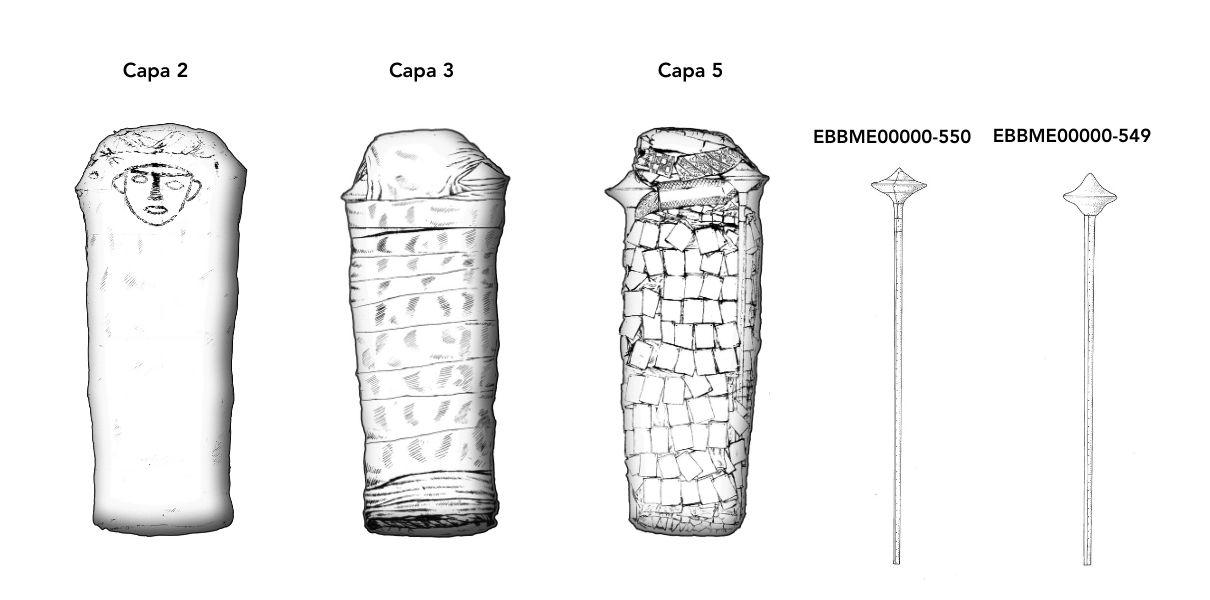

Following the Moche burial pattern, the Lady of Cao’s funerary bundle adopted an elongated form, preserving the extended position of the individual inside. The morphology of the bundle reflects both the multiple textile wrappings and the placement of offerings within. Due to the internal pressure generated, several lateral tears occurred in the textiles, which revealed the heads of two gilded copper maces positioned at each end (Fernández, 2021: 110).

These ornaments, recorded in Layer 5 of the funerary bundle, are considered emblems of power. Although their functions varied depending on their bearers, in the Lady of Cao’s political-religious life the maces fulfilled a symbolic ritual role (Franco, 2021: 339).

Figure 1. Drawings of the unwrapping process by Segundo Lozada. CAEB graphic archive.

Manufacture of the objects: production, decoration, and finishing

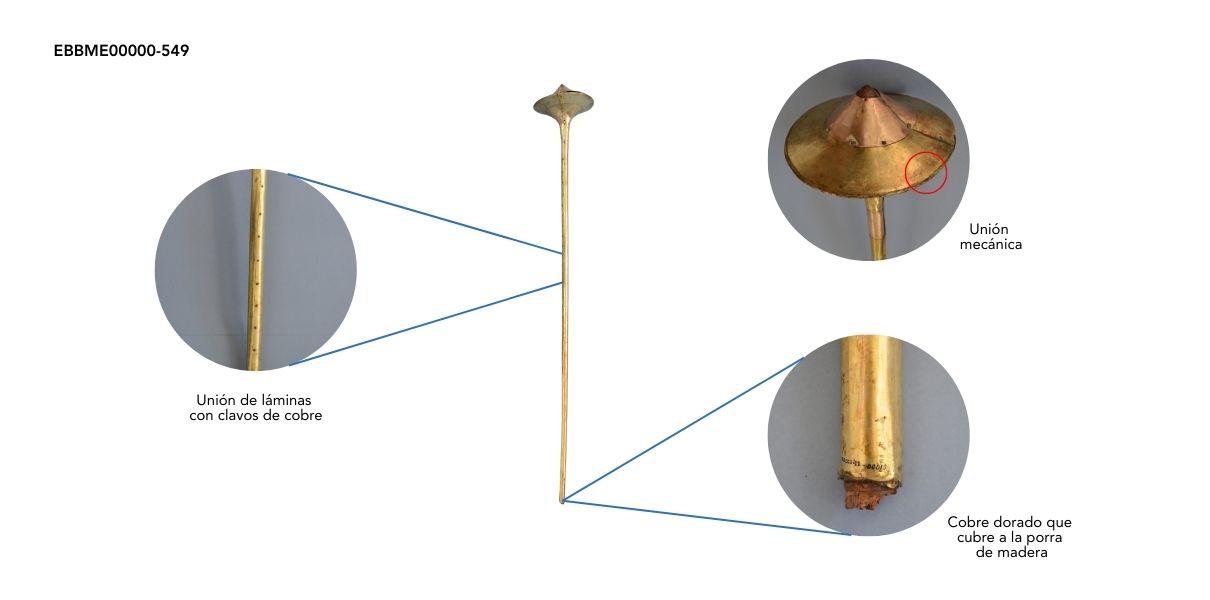

The maces accompanying the body of the Lady of Cao were produced using woodworking techniques for the carved pieces and lamination and cutting techniques for the gilded copper sheets that cover them (Cesareo et al., 2021).

Structurally, these wooden maces feature a distal end in the shape of a double cone, measuring 25 cm in diameter, and a long handle of more than one and a half meters (>1.50 m). However, they differ in decoration: piece EBBME00000-550 is covered with three gilded copper sheets, while piece EBBME00000-549 is covered with seven gilded copper sheets. A relevant aspect of the joining techniques employed is that, in both cases, at the distal end, the copper sheets were joined through mechanical fastening, a technique that allows two or more metal pieces to be connected without altering their chemical composition by means of heat. In addition, on the handle of the mace, the number and section of the copper nails used to secure the sheets to one another can still be observed.

Figure 2. Manufacturing techniques of mace EBBME00000-549.

Findings at Huaca Cao Viejo

Figure 3. Huaca Cao Viejo with its respective buildings and datings from the new research conducted from 2020 to the present. Archives of the El Brujo Archaeological Complex.

Huaca Cao Viejo is a monumental Moche building that records multiple occupational sequences, including construction fills, architectural remodelings, as well as elite burials and domestic spaces (Mujica, 2007).

During the final decade of the 20th century, excavation seasons revealed that, during the closure events of one of the chambers on the west side of the upper platform, corresponding to the second building of Huaca Cao Viejo, several fragmented wooden maces were deposited among the construction fills (Franco et al., 1996). Some of these displayed cut marks or had intentionally broken handles. In these cases, the presence of nails in the pieces suggests that they must have had some type of covering during use (Franco et al., 1999). Their absence indicates that the metal was likely reused to cover or manufacture other objects.

Figure 4. Maces found in closure events: a: EBBBT00000-14 and b: EBBBT00000-479. CAEB photographic archive.

Similarly, associated with the use of the third building at the northwestern summit of Huaca Cao Viejo, mace fragments recorded provided further details regarding the manufacture of these artifacts (Franco et al., 1998). In this case, piece EBBBT00000-480, lacking its upper appendage, revealed two central square-shaped slots that served as fittings for the other half with an additional element. This evidence suggests at least two different manufacturing techniques: (a) single-piece maces and (b) assembled maces.

Figure 5. Mace EBBBT00000-480. CAEB photographic archive.

Would you like to see these pieces up close? visit rooms 4 and 6 of the Cao Museum!

Our museum displays feature the most representative pieces from the El Brujo collection, including wooden maces exhibited in Room 4, as well as the maces that accompanied the Lady of Cao, which are on display in Room 6.

Figure 6. Maces EBBBT00000-15 and EBBBT00000-14 on display in Room 4 of the Cao Museum.

Final Remarks

While Moche iconography frequently depicts war scenes with warriors carrying different combat weapons: atlatls, darts, shields, or maces (Donnan, 2004), it is the archaeological contexts that allow us to study the objects themselves, their materials, manufacturing techniques, and uses. At Huaca Cao Viejo, the burial of maces within construction fills provides insight into the types of maces the Moche used, their state of preservation, and their placement within these contexts, whether as discarded objects or ritual offerings.

Future research will allow us to learn more about the association of each piece with its context, as well as its functionality, typology, and use.

References

Cesareo, R., Franco, R., Fernández, A., Bustamante, Á., Fabián, J., del Pilar, S., Azeredo, S., Lopes, R., Ingo, G., Riccuci, C., Di Carlo, G., & Gigante, G. (2021). Analytical studies on the gold and silver jewelry of the Lady of Cao. In A. Bazán (Ed.), The Funerary Context of the Lady of Cao. Discovery and Research on Moche Elite Burials at Huaca Cao Viejo, El Brujo Archaeological Complex (pp. 234–271). The Wiese Foundation.

Chamussy, V. (2014). Study on weapons of war and hunting in the Central Andean area: Description and use of thrusting and cutting weapons. Arqueología y Sociedad, 27, 297–338.

Donnan, C. B. (1978). Moche Art of Peru: Pre-Columbian Symbolic Communication (First edition). Museum of Cultural History.

Donnan, C. B. (2004). Moche Portraits from Ancient Peru. University of Texas Press.

Fernández, A. (2021). Unwrapping funerary bundles. In A. Bazán (Ed.), The Funerary Context of the Lady of Cao. Discovery and Research on Moche Elite Burials at Huaca Cao Viejo, El Brujo Archaeological Complex (pp. 116–187). The Wiese Foundation.

Franco, R. (2021). Symbols of power in the emblems and metal ornaments of the Lady of Cao. In A. Bazán (Ed.), The Funerary Context of the Lady of Cao. Discovery and Research on Moche Elite Burials at Huaca Cao Viejo, El Brujo Archaeological Complex (pp. 334–359). The Wiese Foundation.

Franco, R., Gálvez, C., & Vásquez, S. (1999). Moche maces from the El Brujo Complex. Archaeological Journal SIAN, 4(7), 16–23.

Franco, R., Gálvez, C., & Vásquez, S. (1996). Archaeological Program El Brujo Complex. Final Report, 1996 Season. Magdalena de Cao: The Wiese Foundation, National Institute of Culture – La Libertad, National University of Trujillo.

Franco, R., Gálvez, C., & Vásquez, S. (1998). Archaeological Program El Brujo Complex. Final Report, 1998 Season. Magdalena de Cao: The Wiese Foundation, National Institute of Culture – La Libertad, National University of Trujillo.

Golte, J. (2016). Moche. Cosmology and Society: An Iconographic Interpretation. Institute of Peruvian Studies.

Kutscher, G. (1983). Nordperuanische Gefässmalereien des Moche-Stils. Munich: Beck-Verlag.

Mujica, E. (Ed.). (2007). El Brujo. Huaca Cao, Moche Ceremonial Center in the Chicama Valley. Lima: The Wiese Foundation.

Pérez, C. (1999). Metal weapons in pre-Hispanic Peru. Space, Time and Form. Series I, Prehistory and Archaeology, 12, 319–346.

Researchers , outstanding news